Jersey Jazzman: The Merit Pay Fairy Dies in Newark

One of the long-running characters on this blog is the Merit Pay Fairy.

Hey, youse bums -- get back to the teachin' already!

The Merit Pay Fairy lives in the dreams of right-wing think tanks and labor economists, who are absolutely convinced that our current teacher pay system -- based on seniority and educational attainment -- is keeping teachers from achieving their fullest potential. It matters little that even the most generous readings of the research find practically small effects* of switching to pay-for-performance systems, or that merit pay in other professions is quite rare (especially when it is based on the performance of others; teacher merit pay is, in many contexts, based on student, and not teacher, performance).

Merit pay advocates also rarely acknowledge that adult developmental theory suggests that rewards later in life, such as higher pay, fulfill a need for older workers, or that messing with pay distributions has the potential to screw up the pool of potential teacher candidates, or that shifting pay from the bottom of the teacher "quality" distribution to the top -- and, really, that's what merit pay does -- still leaves policymakers with the problem of deciding which students get which teachers.

Issues like these, however, are at the core of any merit pay policy. Sure, pay-for-performance sounds great; it comports nicely with key concepts in economic theory. But when it comes time to implement it in an actual, real-world situation, you've got to confront a whole host of realities that theory doesn't address.

Which is what seems to have happened in Newark:

In 2012, Newark teachers agreed to a controversial new contract that linked their pay to student achievement — a stark departure from the way most teachers across the country are paid.

The idea was to reward teachers for excellent performance, rather than how many years they spent in the district or degrees they attained. Under the new contract, teachers could earn bonuses and raises only if they received satisfactory or better ratings, and advanced degrees would no longer elevate teachers to a higher pay scale.

The changes were considered a major victory for the so-called “education reform” movement, which sought to inject corporate-style accountability and compensation practices into public education. And they were championed by an unlikely trio: New Jersey’s Republican governor, the Democratic-aligned leader of the nation’s second-largest teachers union, and Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, who had allocated half of his $100 million gift to Newark’s schools to fund a new teachers contract.

“In my heart, this is what I was hoping for: that Newark would lead a transformational change in education in America,” then-Gov. Chris Christie said in Nov. 2012 after the contract was ratified.

Seven years later, those changes have been erased.

Last week, negotiators for the Newark Teachers Union and the district struck a deal for a new contract that scraps the bonuses for top-rated teachers, allows low-rated teachers to earn raises, and gives teachers with advanced degrees more pay. It also eliminates other provisions of the 2012 contract, which were continued in a follow-up agreement in 2017, including longer hours for low-performing schools. [emphasis mine]

I blogged about that 2012 contract many times as it was being negotiated. It was never popular; only 37 percent of the membership approved it, thanks to low turnout in the voting. The teachers were promised up to $20 million in extra funding, over three years, dedicated to merit pay, all coming from Mark Zuckerberg's famous donation to Newark's schools. But the actual disbursement was far less: only $1.4 million in the first year. And much of that appears to have come from teachers who were denied regular annual raises due to "poor performance."

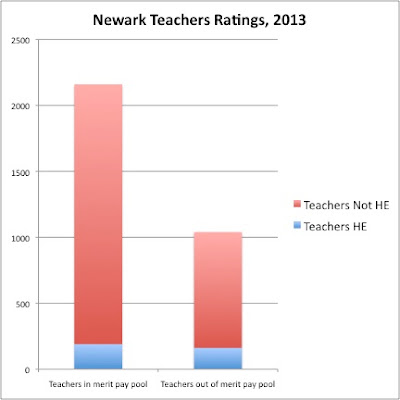

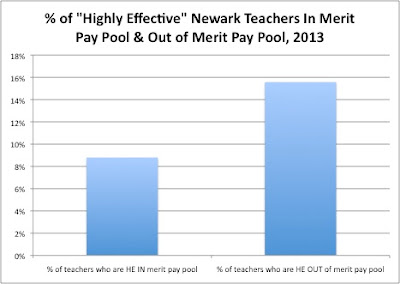

More senior teachers with advanced degrees had the option of not participating in merit pay; only about 20% chose to enter the system, putting to rest any idea merit pay was popular among teachers who had a choice. In addition, the percentage of "highly effective" teachers was much higher in the pool of teachers who opted out of merit pay than those who were in the system.

This pretty much destroys the notion that "better" teachers are clamoring for merit pay; in Newark, many doubted the system would work to their benefit.

This trepidation can be found in a survey of Newark teachers by the American Institutes for Research, which was conducted in the first year of the contract. Over 40 percent of teachers both in and out of the merit pay system believed merit pay would hurt collaboration (p. 25); 60 percent believed the system ignored important aspects of their teaching (p. 24). Nevertheless, over 70 percent believed their pay system was fair and appropriate at their school. My reading of these results is that there was concern over the system, but teachers were willing to give it a shot.

Those of us who follow Newark's schools know what happened next: a mass revolt against the district's administration, which reported directly to the governor at the time, Chris Christie. A mayoral election where state control of schools was the key issue. The return of local control of schools after two decades. And now, the end of Newark's merit pay experiment.

One curious thing about the AIR report: it was labeled as "Year One":

NPS [Newark Public Schools] commissioned American Institutes for Research (AIR) to conduct an evaluation of the implementation and impact of the NPS/NTU contract and associated initiatives. The three-year evaluation focuses on a variety of outcomes (e.g., educator perceptions, teacher retention, teacher effectiveness, and student achievement) associated with the four contract components. In the first year of the evaluation, the period to which this report corresponds, the evaluation team used qualitative and quantitative techniques to assess the implementation of the contract components and to examine the association between the new evaluation and compensation systems (i.e., Components 1 and 2) and teacher retention. This report presents findings related to educator perceptions, as captured by teacher and school leader surveys administered in spring 2015, after two years of contract implementation (i.e., as of the 2014–15 school year) and teacher retention after one year of contract implementation (i.e., through the 2013–14 school year).1 The AIR evaluation team plans to examine the contract’s impact on teacher effectiveness and student achievement in 2016 and 2017, respectively. [emphasis mine]

Guess what? There was ever a follow-up study of Newark's merit pay system. For whatever reason, AIR never published any further reports on whether merit pay helped improve student learning, improved effective employee retention, or improved the quality of new teaching candidates in NPS.

You would think, given all the hoopla over this contract at the time, that a thorough study of how merit pay played out in Newark would have been a top priority for the state, the district, and all of the folks who were connected to the Zuckerberg donation. Alas, we'll never know how this hyped contract affected the district. We'll never know if merit pay in Newark -- perhaps the most high-profile implementation of teacher pay-for-performance in the United States -- actually worked.

Were I cynical, I'd think that the folks behind this system didn't really want to know whether merit pay works. I'd think they want to keep merit pay a policy based on theory, not evidence. Because if Newark turned out like all the other merit pay experiments, it would show, at best, practically small improvements in student outcomes. And the price for that tiny improvement would be a chaotic and impractical system of teacher evaluation and compensation that was always doomed to fail.

Good thing I'm not cynical...

For those of you who weren't with me during the early, snarkier days of this blog: the idea for the Merit Pay Fairy came from a scene in a play by Christopher Durang:

“You remember how in the second act Tinkerbell drinks some poison that Peter is about to drink in order to save him? And then Peter turns to the audience and he says that ‘Tinkerbell is going to die because not enough people believe in fairies. But if all of you clap your hands real hard to show that you do believe in fairies, maybe she won’t die.’ So, we all started to clap. I clapped so long and so hard that my palms hurt and they even started to bleed I clapped so hard. Then suddenly the actress playing Peter Pan turned to the audience and she said, ‘That wasn’t enough. You did not clap hard enough. Tinkerbell is dead.’ And then we all started to cry.”

It really doesn't matter how many deaths the Merit Pay Fairy dies -- some folks just keep clapping harder:

Shavar Jeffries, who led the Newark school board in 2012 and is now president of the national advocacy group Democrats for Education Reform said he is happy to see teachers get more money under the new agreement. But he said it is disappointing that teachers’ performance will no longer automatically influence their pay — a disconnect, he argued, that many families do not support.

“There’s almost no parent in the city of Newark,” he said, “who thinks that there shouldn’t be a relationship between pay and whether you’re actually doing a good job for babies each and every day in the classroom.”

I don't live in Newark, but I think I'm safe in making this statement: there is definitely no parent in Newark who doesn't want a good teacher for their own kid. The question, then, is what are we doing to ensure that every child in Newark -- and, for that matter, every community -- has a well-trained, competent, effective teacher in their classroom.

Taking away money from "bad" teachers and giving it to "good" ones does little to improve the overall effectiveness of the teaching corps. What would help is raising the base pay for teachers so as to close the compensation gap they suffer compared to other professions; that way, we could attract the best possible candidates into the profession and increase the chances that every child has an effective teacher.

What won't help is imposing unfeasible pay-for-performance systems that, time after time, fail to deliver meaningful improvements. Clap as hard as you want -- the Merit Pay Fairy is dead in Newark, and the prognosis in other communities is not good.

* I'm adding this note in anticipation of a counter-argument for merit pay I've seen before: if you include studies in other countries, the effect size of merit pay grows. But these other countries have such different contexts for teaching and worker pay that applying their results to the U.S. is a highly dubious proposition. Further, the effect size is still very small -- again, even under the most generous interpretation of the results. When effects are so small, we are justified in questioning whether the variation is related to the construct; in other words, are there real improvements in learning, or are teachers just slightly pumping up scores through test prep?

No, I'm not going to debate this on Twitter. Write an article or blog post and I'll respond.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.