Jersey Jazzman: What's Really Happening in Camden's Schools?

This latest series on Camden's schools is in three parts:

Part I

Part II

Part III (this post)

I want to wrap up this series of posts about Camden's schools with a look at the latest CREDO report, which the supporters of recent "reforms" keep citing as proof of those reforms' success.

Long time readers know the CREDO reports, issued by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes at Stanford University, have been perhaps the best known of all research studies on the effectiveness of charter schools. The reports, which are not peer-reviewed, look at the differences in growth in test scores between charter schools and public district schools, or between different school operators within the charter sector. CREDO often issues reports for a particular city's or state's charter sector; they last produced a statewide report for New Jersey in 2013.

I and others have written a great deal over the years about the inherent limitations and flaws in CREDO's methodology. A quick summary:

-- The CREDO reports rely on data that is too crude to do the job properly. At the heart of CREDOs methodology is their supposed ability to virtually "match" students who do and don't attend charter schools, and compare their progress. The match is made on two factors: first, student characteristics, including whether students qualify for free lunch, whether they are classified as English language learners (in New Jersey, the designation is "LEP," or "limited English proficient"), whether they have a special education disability, race/ethnicity, and gender.

The problem is that these classifications are not finely-grained enough to make a useful match. There is, for example, a huge difference between a student who is emotionally disturbed and one who has a speech impairment; yet both would be "matched" as having a special education need. In a city like Camden, where childhood poverty is extremely high, nearly all children qualify for free or reduced-price lunch (FRPL), which requires a family income below 185 percent of the poverty line. Yet there is a world of difference between a child just below that line and a child who is homeless. If charter schools enroll more students at the upper end of this range -- and there is evidence that in at least some instances they do -- the estimates of the effect of charter schools on student learning growth very likely will be overstated.

-- CREDO's use of test scores to match students and measure outcome differences is inherently problematic. The second factor on which CREDO makes student matches is previous student test scores. Using these as a match is always problematic, as test outcomes are prone to statistical noise. For now, I'll set aside some of the more technical issues with CREDO's methods and simply note that all tests are subject to construct-irrelevant variance, a fancy way of saying that scores can rise not because students are better readers or mathematicians, but simply because they are better test takers. If a charter school focuses heavily on test prep -- and we know many of the best-known ones do -- they can pump up effect sizes without increasing student learning in a way that we would consider meaningful.

-- The CREDO reports translate charter school effects into a "days of learning" measure that is wholly unvalidated. I've been going on about this for years: there is simply no credible evidence to support CREDO when they make a claim about a charter school's students showing "x number of days more learning" than a public district school's students. When you follow CREDO's citations back to their original sources, you find they are making this translation based on nothing. It's no wonder laypersons with little knowledge of testing often misinterpret CREDO's results.

Again, I and others have been writing about these limits of the CREDO studies for years. But the Camden "study" has some additional problems:

First, it's not really a "study" -- it's a Powerpoint slideshow that is missing some essential elements that should be included in any credible piece of research. Foremost of these is a description of the variables. In previous reports, CREDO at least told its readers how the percentages of FRPL, special education, and LEP students varied between charter and public district schools. But they don't even bother with this basic analysis here. And it's important: if the charter sector is taking proportionally fewer of the students who are more challenging to educate, they may be creating a peer effect that can't be scaled up.

Second, free and reduced-price lunch (FRPL) is an even less accurate measure of student socio-economic status when a district has universal enrollment in the school meal program. If a student's family knows she will automatically receive a free meal, they will have less incentive to fill out an application. We've seen significant declines in the percentage of FRPL students in some districts that have moved to universal enrollment, indicating this is a real phenomenon.

In contrast, New Jersey charter schools get more funding when they enroll a FRPL-eligible student. They have an incentive to get a student's family to fill out an application that the district does not. Did CREDO account for this? They don't say.

Third, the switch in tests in 2015 complicates any test-based analysis. There are at least two reasons for this: first, the previous test scores of students in both the charter and public district groups go back to 2014, when the NJASK was the test. As Bruce Baker and Ishowed in our analysis of Newark's schools, there is evidence that schools made a sudden shift in their relative standing on test outcomes when the switch in tests occurred. Shifts this fast are almost certainly not due to changes in student instruction; instead, they occur because some students were more familiar with the new format of the test than others. This, again, puts the matching process in doubt.

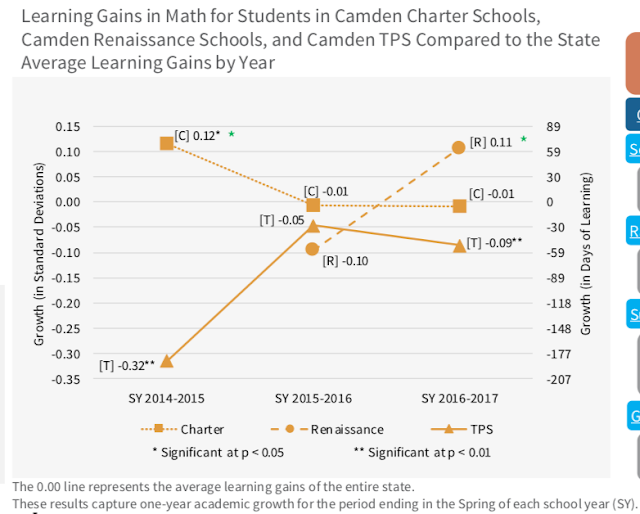

The second reason is related to the first: some schools likely took longer to acclimate to the new test than others. Their relative growth in outcomes, therefore, will probably shift in later years. Did that happen in Camden? Let's look at some of the CREDO report's results:

As I explained in earlier posts, there are three types of publicly-funded schools in Camden: Camden City Public Schools, denoted here as "TPS" for "Traditional Public Schools"*: independent charter schools; and renaissance schools, which are operated by charter management organizations (CMOs), and are supposed to take all students in a neighborhood catchment zone (but don't -- hang on...).

Note here that CCPS schools made a leap in relative growth between 2015 and 2016. Do you think it's because the schools got so much better in one year? Or is it more logical to believe something else is going on? A more likely explanation is that Camden students were not well prepared for the change in test format in 2015, but then became more familiar with it in 2016. It's also possible the charter students were better prepared for the new test in 2015, but lost that advantage in 2016, when their relative growth went down.

This is all speculation... but that's the point. Sudden shifts in test score outcomes are likely due to factors other than better instruction. Making the claim, based on sudden shifts in outcomes, that any particular sector of Camden's school system is getting better results due to their practices is a huge leap -- especially when we now know something important about the renaissance schools...

Because renaissance schools are not enrolling all students in their neighborhoods, their students are different from CCPS students in ways that can't be captured by the data. Here, again, is the State Auditor in his renaissance school report:

- The current enrollment process has limited the participation of neighborhood students in renaissance schools. Per N.J.S.A. 18A:36C-8, renaissance schools shall automatically enroll all students residing in the neighborhood of a renaissance school. Instead, the district implemented a centralized enrollment system in which families must opt in if they prefer to attend a renaissance school. This process has left the district with fewer than half of neighborhood students being enrolled in their neighborhood renaissance school.

- [...]

- The current policy could result in a higher concentration of students with actively involved parents or guardians being enrolled in renaissance schools. Their involvement is generally regarded as a key indicator of a student’s academic success, therefore differences in academic outcomes between district and renaissance students may not be a fair comparison.

As I said in the last post, it is very frustrating that the State Auditor gets this, but people who proclaim to have expertise in education policy do not. Let me state this as simply as I can:

A "study" like the Camden CREDO report attempts to compare similar students in charters and public district schools by matching students based on crude variables. Again, these variables aren't up to the job -- but just as important, students can't be matched on unmeasured characteristics like parental involvement. Which means the results of the Camden CREDO report must be taken with great caution.

And again: when outcomes suddenly shift from year-to-year, there's even more reason to suspect the effects of charter and renaissance schools are not due to factors such as better instruction.

One more thing: any positive effects found in the CREDO study are a fraction of what is needed to close the opportunity gap with students in more affluent communities. There is simply no basis to believe that anything the charter or renaissance schools are doing will make up for the effects of chronic poverty, segregation, and institutional racism from which Camden students suffer.

Now, there are some very powerful political forces in New Jersey that do not want to acknowledge what I am saying here. They want the state's residents and lawmakers to believe that the state takeover of Camden's schools, and subsequent privatization of many of those schools, has led to demonstrably better student outcomes -- so much better that upending democratic, local control of Camden's schools was worth it.

Remember: the takeover and privatization of Camden's schools was planned without any meaningful local input. From 2012:

CAMDEN — A secret Department of Education proposal called for the state to intervene in the city’s school district by July 1, closing up to 13 city and charter schools.

[...]

The intervention proposal, which was obtained by the Courier-Post, was written by Department of Education employee Bing Howell.

He did not respond to a phone call and email seeking comment.

Howell serves as a liaison to Camden for the creation of four Urban Hope Act charter schools. He reports directly to the deputy commissioner of education, Andy Smerick.

Howell’s proposal suggests that he oversee the intervention through portfolio management — providing a range of school options with the state, not the district, overseeing the options. He would be assisted by Rochelle Sinclair, another DOE employee. Both Howell and Sinclair are fellows of the Los Angeles-based Broad Foundation. [emphasis mine]

A California billionaire paid for the development of a "secret" (that's the local newspaper's word, not mine) proposal to wrest democratic, local control of schools away from Camden and develop a "portfolio" of charter, renaissance, private, and public schools. This proposal fit in nicely with the plans for Camden's redevelopment, which, as we are now learning, included a series of massive tax breaks for corporations with ties to the South Jersey Democratic machine.

The same forces that are now trying to justify this tax giveaway are the same forces that pushed forward a radical transformation of Camden's schools. They would have us all believe that this transformation is as "successful" as their tax schemes.

But in both cases they are relying on the flimsiest of evidence, badly interpreted and devoid of any meaningful context. The case for educational "reform" in Camden is as weak as the case for corporate tax incentives in Camden.

Camden's families deserve what so many suburban families in New Jersey have: adequately funded and democratically, locally controlled schools. Small, dubious bumps in student growth found in incomplete "studies" are not an acceptable substitute.

That's all, for now, about Camden. We'll move on to another state next...

* I don't use "TPS" because I think it's a loaded term: the word "traditional" can carry all sorts of unwarranted negative connotations. CCPS schools are properly defined as "public district schools."

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.