Jersey Jazzman: Is "No Excuses" Narrowing the Curriculum? Evidence from Newark

This post is part of a series on recent research into Newark schools and education "reform."

Here's Part I.

Here's Part II.

This is Part III.

* * *

Just a few more thoughts about the recent research Bruce Baker and I did on Newark, one of the most prominent test cases of education "reform" to emerge in recent years.

We wrote our research brief, published by the National Center for Education Policy, as a response to recent research by a team of Harvard economists that (to state it briefly) purports to show how moving students from "low-performing" public schools to "high-performing" charters lifted the overall outcomes of students in Newark.

However, as Bruce and I point out: the gains were quite small, they appear to be completely tied to a change in exams (from the old NJASK to the PARCC), and other districts in Essex County, NJ showed similar results. So it's not as if there is much for the supporters of "reform" in Newark, including Mark Zuckerberg, to crow about here.

Still, there's an interesting question that arises in studying the Newark "reforms," or any other educational intervention: what, exactly, are the (small) test score gains really indicating?

It so happens that as I was writing our report, I was also reading Daniel Koretz's excellent new book, The Testing Charade. One of the central arguments Koretz makes is that focus on test outcomes can distort educational programs to the point where:

- The "learning" that takes place in a test prep environment amounts to little more than pedagogical shortcuts that might increase test scores, but aren't reflective of deepening knowledge.

- Non-tested subjects -- history, lab sciences, civics, music, art, physical education, etc. -- are given short shrift.

As a music educator, the second point is the one that concerns me the most. Charter school marketeers like Eva Moskowitz will tell us over and over how rich and deep her schools' curriculum is ("Chess! We have chess!"), but as I showed last year, the plain fact is these schools do not come anywhere close to offering what affluent suburban schools offer.

But how do charters compare to their neighboring urban district schools? Do charters sacrifice instruction in non-tested subjects? Do they offer less programming in, say, the arts compared to their host districts -- keeping in mind that arts offerings in urban district schools are often considerably less expansive than those in more affluent communities?

I'll be the first to say this is a big topic and the data we have isn't going to give us a definitive answer. But there are clues -- good clues -- that suggest charters may not be putting as many resources into non-tested area instruction as public district schools.

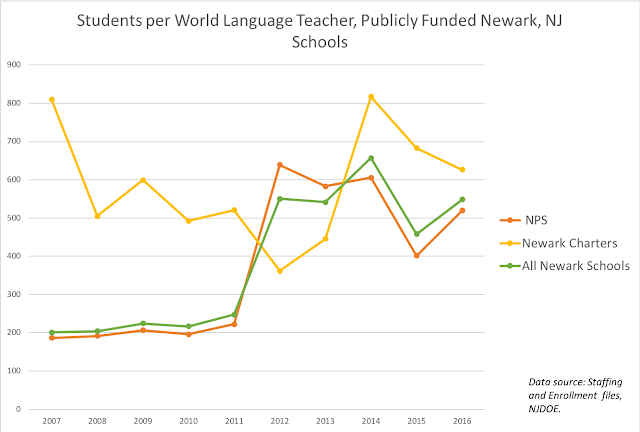

We have access to what are known as "staffing files" for all publicly-funded schools in New Jersey, both district and charter. The files list characteristics of every certificated school staff member in the state (yes, I'm in there also). One of those characteristics is the "job code," which is related to the subject area for which a teacher receives a certificate. I, for example, am listed as a "music teacher," and my certification says I have met the requirement to be considered competent to teach in that subject.*

Because we can determine the number of staff with particular certifications, and because we know the numbers of students enrolled at a school, we can calculate the "student load" for teachers in different subject areas. This gives us, arguably, an indication of how expansive programming in particular subjects could be. For example: if one school has enough art teachers that each teacher has a "load" of 400 students, we would expect the school to offer more art than a school where teachers have a "load" of 800.

There are some caveats that go along with this. Comparing schools with different grade levels, for example, becomes problematic, as school systems might rationally decide that the teachers of older students may be able to offer high-quality programming even with a greater "load" than teachers of younger students. Still, this is a good first step for our purposes.**

So let's look at the data. How, for example, does the deployment of arts teachers compare between the Newark Public Schools and the city's charter sector?

Year after year, Newark's charters provide their students with fewer art teachers per student, compared to NPS. There are some pretty wild swings in the data for the charters (NPS is quite steady). Historically, however, the charter sector just hasn't deployed as many personnel toward teaching art as the public, district schools.

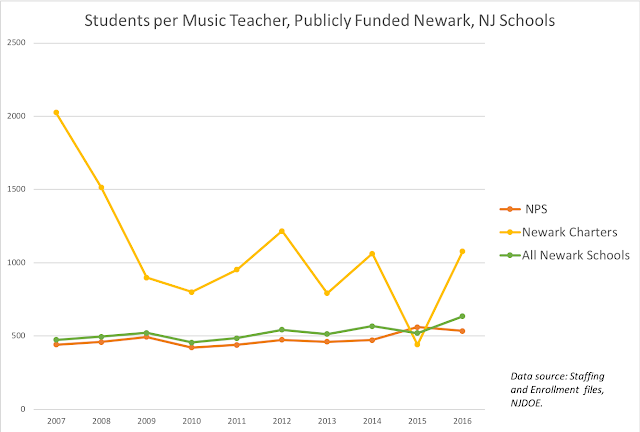

Let's look at some other examples. Music:

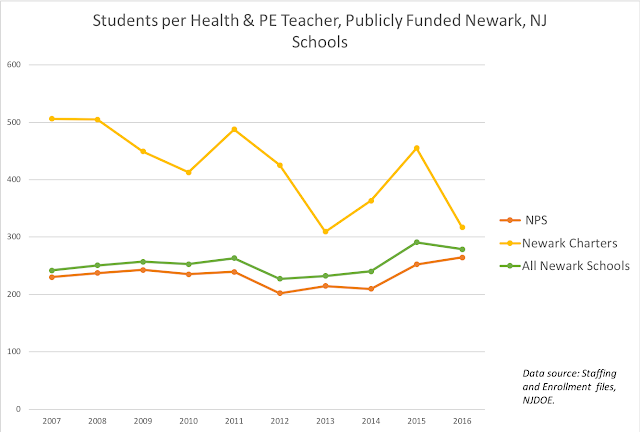

Physical education:

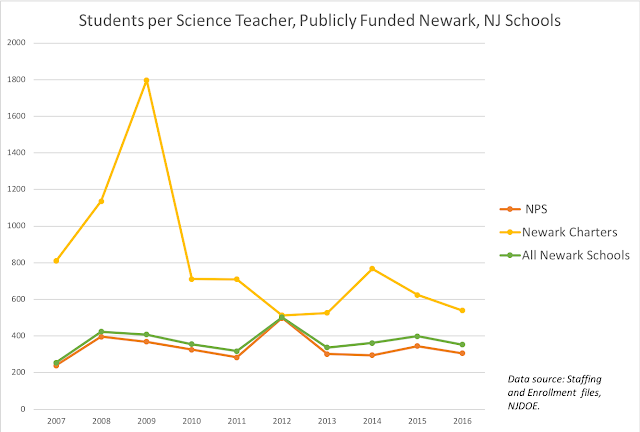

Science:

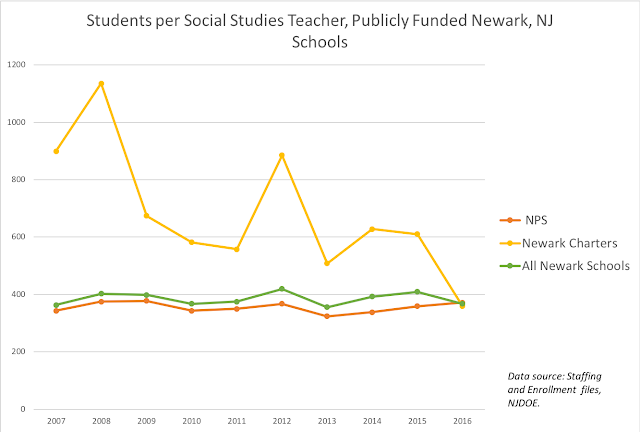

Social Studies:

World Languages:

Again, there are some big swings. But the general pattern in Newark is that the charter schools historically have tended to deploy fewer teachers per pupil in non-tested subjects compared to NPS.

And when you think about it... how could they? Even the largest charter chains -- TEAM/KIPP and Uncommon/North Star -- have small enrollments compared to the size of NPS. Scale issues can make it hard for a charter school to offer all the programming a large school district can. And the mom-and-pop charters just don't have the numbers of kids to justify keeping a full-time music teacher AND an art teacher AND a PE teacher AND foreign language teachers on staff.

But more than that: as Koretz points out in his book, the leaders of the big charter chains all admit they place great value on test outcomes -- hell, they've written entire books about it. Doesn't it stand to reason that they'd sacrifice non-tested subject instruction if that meant better test scores? Given their own words, isn't this kind of staff deployment exactly what we'd expect to find?

Again: I don't pretend this is the last word on the subject. But I think this is more than enough evidence for charter regulators to start taking a close look at the entire curriculum within these schools. If we really believe that all children should have a rich, deep education in many domains of learning, shouldn't we make sure that schools funded with taxpayer monies are doing just that?

That's enough about Newark for now... time to think about some other things...

* Among other things, getting a certificate requires a certain amount of college-level coursework specific to a subject; for example, I had to have a designated number of credits in music. You also have to pass a subject-specific test, like the Praxis.

** I continue to work on this technique, which I have used before in similar research. Early indications are the grade level a charter serves doesn't have a big effect on these ratios... but this is, admittedly, work in progress.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.