Yong Zhao: Did the Shift from Paper to Computer Bring Down East Asia’s (China’s) PISA Performance?

I was surprised by China’s 2015 PISA performance, particularly in reading. I was confident that even the expansion beyond Shanghai would not cause a significant decline based on my understanding of the Chinese education system. And Beijing, Jiangsu, and Guangdong are traditionally strong performers in China, and among the most developed provinces, although behind Shanghai.

While I don’t believe PISA scores mean anything beyond the ability to perform on PISA tests, I wanted to see if I needed to change my thinking. Perhaps Chinese students are not as good at taking tests as I had thought? Perhaps students in Shanghai are drastically different from the rest of China? Perhaps China’s education system is changing very fast that they have truly moved away from test preparation? I am willing to consider any possibilities in the face of evidence.

I found a news article from Chinese Taipei (Taiwan), whose reading performance has declined significantly as well, although not as much as China (Shanghai to BSJG). Chinese Taipei’s reading ranking dropped from #8 in 2012 to #23 in 2015. According to the report from Chinese Taipei’s Central News Agency, a high-level official of its Ministry of Education attributed the decline to students’ unfamiliarity with reading on a computer. Because PISA changed from paper-based to computer-based tests. Although students in Taiwan may use smart devices for other purposes, they are not used to reading large amount of text, diagrams, and graphics on a computer screen. The official said in addition to improve reading in general, Taiwan would increase computers to support reading and adding computer-based tests to important exams in the future.

Seems a reasonable hypothesis. PISA shifted from paper-based tests to computer-based tests from 2012 to 2015 for most participants.

So I dug a little bit deeper. First I verified that indeed all students in China (BSJG) took the PISA on computers (looks like Windows-based laptops), which are very different from what most young students are using today (hand held devices), if they had access to digital devices. Second, I confirmed that the percentages of students categorized as rural are much higher in Beijing, Jiangsu, and Guangdong than Shanghai. That rural students have less access to technology is a safe assumption. So these students would be less familiar with computers. Finally, it is also common in China that many parents and teachers do not want their students to spend much time on the computer as they view it as a distraction from real study. It is thus unreasonable to assume the new student population representing China is not familiar with reading and taking tests on computers.

This may be true in all Asian systems. Although Korea, Japan, Hong Kong, and Singapore have all put much emphasis and invested heavily in educational technology (see my report Lessons that Matter: What Should We Learn from Asia’s School Systems). It is likely that students are still more used to doing school work on paper. While I am not able to find much evidence to confirm this hypothesis, I think it is likely based on my analysis of the changes in PISA scores across different cycles. All data are from NCES PISA Site (PISA Data Explorer).

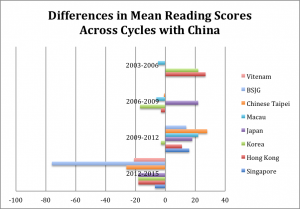

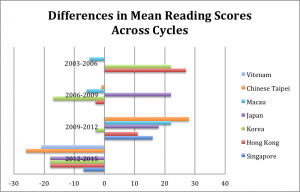

First, all East Asian systems’ saw a decline in reading from 2012 to 2015, some are very significant, in contrast to the increase shared by almost all systems except Korea between 2009 and 2012. Previous cycles showed some increase and some loss (see Figures below).

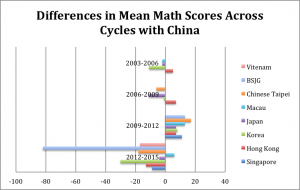

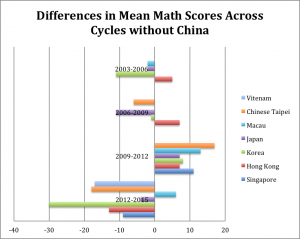

Second, we see almost an identical pattern for math. Except for Macau, which had a modest increase, all other East Asian system saw a decline, most statistically significant, including Singapore (yes, the #1 Singapore) from 2012-2015. In contrast, the changes across 2009-2012 are all positive (Figures below).

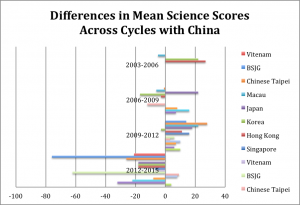

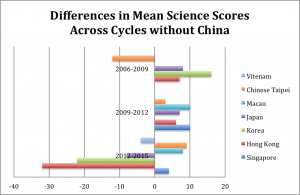

Third, the situation in science is a bit more mixed, but still shows the majority of East Asian systems’ performance declined significant in 2015 from 2012. Singapore, Macau, and Chinese Taipei had some modest gains. However, all East Asian systems saw an increase in science scores, even the best performer Shanghai gained points from 2009 to 2012. (Figures below).

What could have caused such a uniform change in eight education systems in as short a time as three years? The only common factor I could find is the change of PISA delivery format: from paper to computer.

PISA did pay attention to the issue and make it possible to compare the 2015 computer-based results with paper-based tests in previous cycles, according to its report. However, whether the effort on tweaking items enough to offset the impact on populations of students who are not used to reading and doing tasks on a computer remains a question that PISA should answer.

Until we have the answer, I hope we do not jump to conclusions such as: After all, China’s education is not as great as we thought, based on Shanghai’s performance, or East Asian’s PISA performance is in decline, or East Asian students are not good at taking tests anymore, or perhaps East Asian countries education reforms are becoming successful so they are not as focused on test preparation as before (which I hope can indeed happen). Again, my advice: Don’t read too much into it.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.