Jersey Jazzman: Thoughts On Question 2 and Charter School Expansion

As we enter the final days of the election, the debates have intensified -- and not just over whether we should give the nuclear codes to an unqualified, misogynistic, racist maniac...

In Massachusetts, a battle is being waged over Question 2, a proposal to lift a statewide cap on the expansion of charter schools. Like many of the debates over charter expansion and educational "choice," much of the rhetoric revolves around the ostensible "gains" that charter students make compared to students who are in public district schools.

But the Q2 debate is unique: a group of academics, many affiliated with MIT, have been following the expansion of charter schools in and around Boston for years. I can't think of another region where charter schools have been studied so closely using econometric methods. This work has been at the heart of the policy discussion of Q2; it’s cited repeatedly in reports about the ballot initiative.

And the economists who conducted this research have been happy to help make the case that their studies support lifting the cap:

As policies are debated, we often have to rely on research that is ill-suited to the task. Its methodology is frequently too weak to form a firm foundation for policy. Or, the population, design, and setting of the research study are so different from the policy in question that the findings cannot be easily extrapolated.

This is not one of those times. We have exactly the research we need to judge whether charter schools should be permitted to expand in Massachusetts. This research exploits random assignment and student-level, longitudinal data to examine the effect of charter schools in Massachusetts. [emphasis]

Do we? Do these studies tell us exactly what we need to know about whether Massachusetts should lift its cap on charter expansion?

Because simply showing that charter school students in Boston get better test scores than similar students in the Boston Public Schools is not, I'm afraid, nearly enough evidence to support lifting the cap. In fact, the more time I spend looking at this research, the more questions I have about whether Massachusetts can reasonably expect charter expansion to improve its schools:

- Are the students who enter charter lotteries equivalent to the students who don't? This is a critical limitation of these studies that is often ignored by those who cite them. The plain fact is that the very act of entering your child into a charter school lottery marks you as different from the rest of the population; you are taking an affirmative step the majority of public school parents are not taking in an attempt to improve your child's education. There's a real likelihood your family is not equivalent to a family that doesn't enter the lottery.

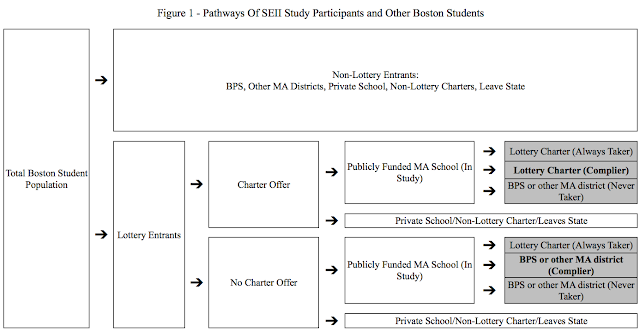

Here's a diagram from a report I coauthored with University of Wisconsin professor Julie Mead:

If the target population is all Boston students, we have to acknowledge the samples from the lottery studies are missing many of them. And it's not just students who don't enter the lottery; what about students who enter, don't earn a seat, and subsequently move to, say, a private school?*

Here's another look at the issue. This is quick and dirty but it makes my point:

It's not always clear how to calculate the overall target population in these studies; I used the Ns that made the most sense to me.** But even if we're not quite sure about the exact numbers, the scope of the issue is clear: the study sample is only a fraction of the total population. Which would be fine -- if the sample was randomly drawn from the target population.

But clearly, that's not the case: The sample is self-selected, because families have to choose to enter the lottery. Which means the results of the study can only be generalized to that population, because there may be characteristics of the students in the sample that are different from the entire Boston population and affect test scores.

Now, there is one thing researchers can do to mitigate this problem: compare the measurable student characteristics of the study sample and the target population. But there's an issue with doing this, because the metrics used to measure things like economic disadvantage aren't really up to the task.

Ironically, we know this thanks to the work of Sue Dynarski, one of the authors of the lottery studies and the coauthor of the paragraph above. According to Dynarski, crude dichotomous measures like free lunch-eligibility mask significant differences in socio-economic status. So we can't truly determine whether the family characteristics of students in charters are equivalent to those in BPS.

But even if we could, I would still say it wouldn't tell us what we really need to know. It's the unobserved characteristics that probably count here, especially parental involvement and support. Charters often require things like family contracts and time commitments that not all parents can adhere to. The only practical way to account for this is random assignment to treatment: not after entering the lottery, but before.

- Are the effects of charter schools due to their "charteriness"? All of the above said, I still think it's clear that something is going on in Boston's charters. If, however, they are going to be scaled up, it's important to ask not just who gets the gains, but why.

Many of the MIT lottery studies cite Thernstrom and Thernstrom's No Excuses: Closing the Racial Gap in Learning for a qualitative description of the inner workings of charters. The truth, I'm sorry to say, is that this book is not a serious piece of research; it's a political document whose methods would be questionable if they were actually documented.

In the most recent lottery study (Cohodes, Setren & Walters, 2016), the authors describe Boston's charters this way:

The potential for sustained success at scale is of particular interest for “No Excuses” charter schools, a recent educational innovation that has demonstrated promise for low-income urban students. These schools share a set of practices that includes high expectations, strict discipline, frequent teacher feedback, high-intensity tutoring, and data-driven instruction.

First of all, how do we know the charters are any different than the traditional public schools regarding these school practices? Angrist, Pathak & Walters (2012) surveyed charters for their practices, which is fine... except we don't really know how they compare to the public district schools. If we're going to ascribe effects to these practices, we should know how they differ across our treatment and control schools.

We can say, however, that the charters have longer school days and years. This is probably a significant contributor to any effects the charters show. But is it necessary to expand charters to lengthen instructional time? Can't Boston just do that in its district schools?

Probably not easily, because the charters have another big difference with BPS schools:

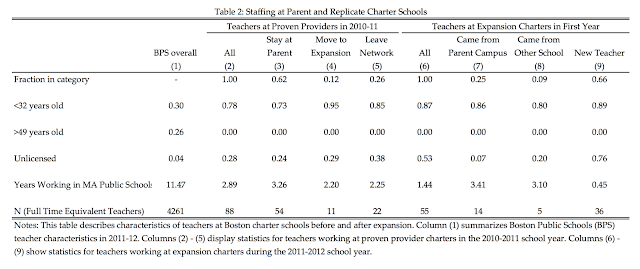

From Cohodes, Setren & Walters (2016). The teachers at the charters studied have far less experience than BPS teachers. In fact, the charters don't have even one teacher over the age of 49. As I've noted in my studies of New Jersey charters, a staff with less experience means less expense; that, in turn, means you can pay staff more to have more instructional time, but still keep your overall costs low.

There's a good argument to be made that it's unrealistic to expect public schools, subject to collective bargaining agreements, to deploy this staffing strategy. Which brings up my third question...

- Can the strategies that make charters "successful" be brought up to scale? Here's a graph based on the table above.

The study only looks at middle schools, and the BPS number above appears to be for all grades within the district. Still, the scope of the issue is apparent: as the charters take more market share, they are going to have to hire a lot more teachers. Will they still be able to attract young, educated people to work in their schools? And will they retain their current teachers, or will they churn-and-burn their staffs? If there's going to be a lot of turnover, the demand for new staff will be even greater than expansion by itself would require.

Boston is renowned for its colleges, so there are plenty of well-educated young people in its workforce. But can the city really continue to supply what the charters need for their staffs if the cap is lifted?

Furthermore, is this good for the teaching profession, and students in urban schools, in the long run? Does Boston really want to be known as a place that hires many inexperienced teachers that leave after a few years? We know teachers gain in effectiveness as they gain more experience; is churn-and-burn really a good model that deserves replication on a wide scale?

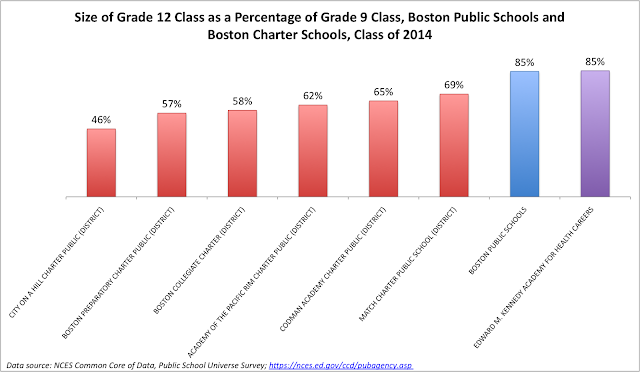

In addition: as I pointed out before, there are patterns of significant cohort attrition within Boston's charter high schools:

There are two possibilities for this pattern. First, the charters may be shedding students, which calls into question the viability of expanding their enrollment. However, as a reader of mine recently argued, maybe the charters are retaining students, giving them an extra year of enrollment to catch them up. OK...

Is Boston ready to spend much more on its schools so it can retain even more students? How much more will this cost? Has anyone looked into this?

This last question is yet another reason I can't agree with Dynarski when she says we have exactly the research we need to be confident Q2 will lead to better education for all of Boston's students. Yes, I agree that the charters are working for many, if not most, of the students they enroll -- at least so far as we can measure based on test scores and other quantifiable outcomes. But there are serious questions as to whether lifting the cap will bring gains that are worth the costs -- questions that cannot be answered by lottery studies.

And, yes, there are costs. As this clever model developed by a couple of public school parents shows, districts can't easily absorb the costs of charter expansion, which is why the state offers extra funds. Unfortunately, the state has not fully funded this program in recent years; if they can't find the money now, how will they find even more funding in the future?

We know that charters place fiscal burdens on hosting districts, largely because they educate students who would otherwise go to private school and they replicate administrative and other costs by creating multiple systems of school governance. We know that charters are not held to the same standards of transparency and accountability as public district schools, because they are not state actors. This has created major problems in other states, incentivizing behaviors that are not in the public's interest.

Is it not possible, given all this, that Boston's charters are getting good results because of the cap? That limiting their expansion has increased quality and stopped the abuses that have plagued states like Michigan, Ohio, and Florida, which have let charter expansion run wild?

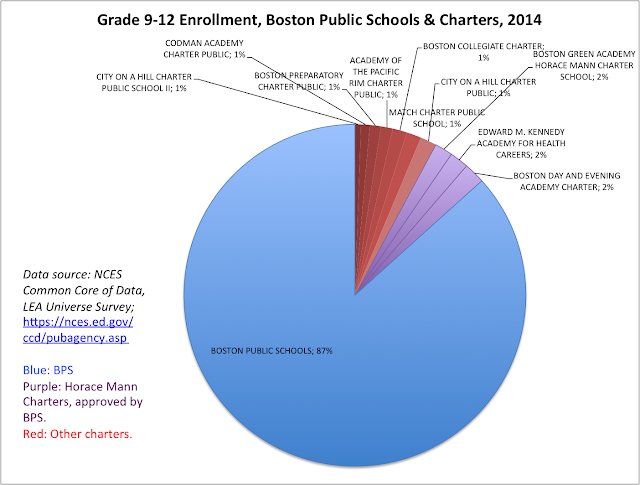

I've seen plenty of folks on social media cite Cohodes, Setren and Walters (2016) as proof that charter expansion will work in Massachusetts. I'd point out that the study is only measuring effects in middle schools, and, again, the enrollments are only a fraction of what they will be if the cap is removed.

This chart uses data from the same year as the last year of their study. The high school market share is still quite small, and a significant portion is in Horace Mann charters, which are controlled by the hosting district. It may well be that the cap has kept Boston from reaching a tipping point where the damages wrought by rampant charter expansion can no longer be contained.

I want to be clear about something: I think these lottery studies are well worth considering. I have great respect for the economists who have been doing this research. Josh Angrist's books sit on my shelf (well, OK, my Kindle).

But the work they've done is limited, so no -- we don't have exactly the research we need to state confidently that lifting the cap will be worth the costs. You wouldn't know that to read the popular press accounts of these studies, but it's true nonetheless.

I understand Boston's children can't wait any longer for real improvement in their schools and their lives. But lifting the cap largely on the basis of these limited studies is not, in my opinion, smart public policy. The good people of Massachusetts have every right to question whether voting yes on Q2 is in the best interests of students both in and out of charters, and to consider the limits of the evidence presented to them as they make their decision.

See you in the Infinite Corridor...

ADDING: I can always count on a group of reformy types to criticize my stuff without apparently reading it. Just to be clear:

According to the NCES Private School Survey, there are 4,558 students enrolled in private schools with a Boston address. It is, of course, impossible to know how many of those had applied to charter schools and then, after not being offered a seat, enrolled in a private school. But, as Bifulco and Reback (2012) note (p.2):

Charter schools can generate excess costs for a number of reasons. First, charter schools can be expected to attract some number of students from private schools (Buddin, 2012; Toma, Zimmer, & Jones, 2006; Ludner, 2007). The additional resources that charter schools use to educate these students are not necessarily new resources from the point of view of society. Nonetheless, transfers from private to charter schools do shift educational costs from the private schools and their parents to the public sector and taxpayers, and thus, create fiscal impacts for public education systems. [emphasis mine]

You can, of course, dispute the scale of this. But there is a sizable population of private school students in Boston. It's hardly unreasonable to bring this up.

UPDATE:

I see I've kicked up quite a bees nest among economists and others who are inclined to support Q2. Let me add a few thoughts from some other folks on the utility of charter school lottery studies.

McEwan and Olsen (2010), from Taking measure of charter schools: Better assessments, better policymaking, better schools. R&L Education. (p.103).

Here's Bruce Baker:

The other type of study is often referred to as meeting the gold standard – as being a randomized study – or lottery-based study. It is assumed, since these studies are declared golden, that they therefore necessarily resolve both above concerns. And it is possible, that if these studies truly were randomized (or even could be) that they could resolve the above concerns. But they don’t (resolve these concerns), because they aren’t (really randomized).

First, what would a randomized study look like? Well, it would have to look something like this – where we randomly take a group of kids – with consent or even against their will – and assign them to either the charter or traditional school option. The mix of kids in each group is truly random and checked to ensure that the two groups are statistically representative (using better than the usual measures) of the population. Then, we have to make sure that all other “non-treatment” factors are equivalent, including access to facilities, resources, etc. That is, anything that we don’t consider to be a feature of the treatment itself. This is especially important if we want to know whether expanding elements of the treatment are likely to work for a representative population. This is a randomized, controlled trial.

So then, what’s randomized in a randomized charter school study? Or lottery-based study? One might sketch out a lottery-based study as follows:

Here, the study is really only randomized at one point in a long complicated sequence – the lottery itself. Students and families have to decide they want to enter the lottery – that they are interested in attending a charter school, which will ultimately affect the composition of the charter school enrollments. Then, among those selecting into the pool, students are randomly chosen to attend the charters along side others randomly chosen to attend (from a non-random pool of lottery participants), and the others randomly selected, to go, well, somewhere else… with a group of peers non-randomly chosen to end up in that same somewhere else.

So, while the studies compare the achievement of kids randomly chosen to those randomly un-chosen (thus comparing only those who tried to get a charter slot), the kids are shuffled into settings that are anything but randomly assigned, containing potentially vastly different peer groups and a variety of other differences in setting. Add to this the likelihood of non-random student attrition, further altering peer group over time.

As such, I very much prefer these studies to be referred to as “lottery-based” rather than randomized or experimental. These studies are randomized at only one step in this process, potentially conflating setting/peer effects with treatment effects, thus substantially compromising policy implications.

As with those matching studies, the types of variables used to check and/or correct for peer composition and non-randomness of attrition are often too imprecise to be useful.

* There's also the matter of compliance with treatment and the use of instrumental variables in these studies' regressions. It's a complex issue that I'll have more to say about later.

** The studies will give "BPS students" as a number for comparison, but it isn't always clear whether charter enrollments are included. I tried to get this as accurate as I could, but, as always, caveat regressor.

Please note that during the election season, many posts indicate preferences for candidates. NEPC, in republishing such posts, is not endorsing those views.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.