The Becoming Radical: Ignoring Poverty in the U.S. Redux: A Reader

We were in Rye, passing the First Church, and the breeze from the ocean was already strong. A man with a great stack of roofing shingles in a wheelbarrow was having difficulty keeping the shingles from blowing away; the ladder, leaning against the vestry roof, was also in danger of being blown over. The man seemed in need of a co-worker—or, at least, of another pair of hands.

“WE SHOULD STOP AND HELP THAT MAN,” Owen observed, but my mother was pursuing a theme and, therefore, she’d noticed nothing unusual out the window….

“WE MISSED DOING A GOOD DEED,” Owen said morosely, “THAT MAN SHINGLING THE CHURCH—HE NEEDED HELP.”

A Prayer for Owen Meany, John Irving

I wrote Ignoring Poverty in the U.S. to reject the decades-long focus on education reform targeted in-school only accountability driven by ever-new standards and high-stakes testing.

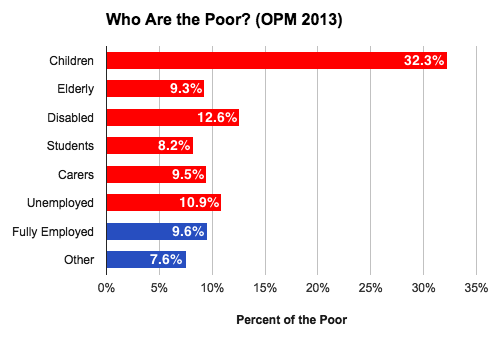

But that work also reveals the incredible power of stereotypes about adults and children living in poverty in the U.S. Despite our cultural myths about rugged individualism and boot-straps success, the impoverished in the U.S. are overwhelmingly vulnerable populations.

- Who is poor in the United States? Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, Lauren Bauer and Ryan Nunn

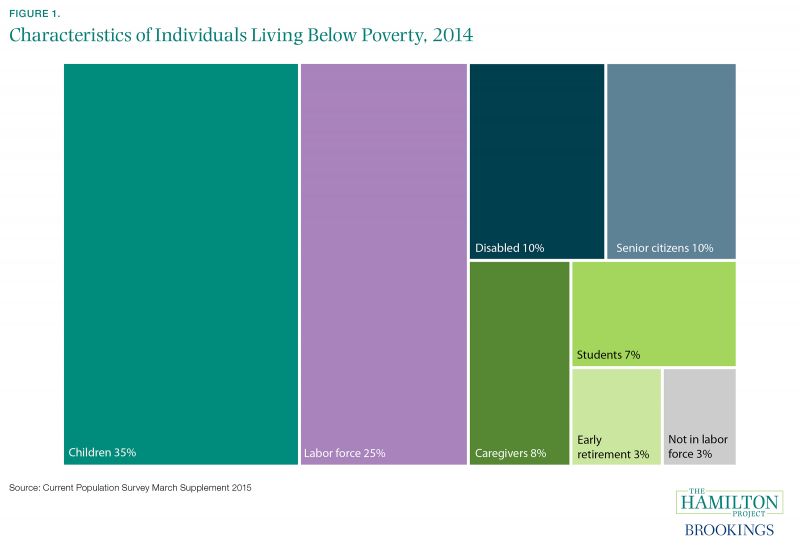

Consider the following sobering statistics, illustrated in the figure above:

- More than a third of those who live in poverty are children. More than 15.5 million children lived in poverty in 2014.

- About 13 percent of those living in poverty are senior citizens or retired.

- A quarter of those who live in poverty are in the labor force—that is, working or seeking employment.

- A tenth of those in poverty are disabled.

- Eight percent of those living in poverty are caregivers, meaning that they report caring for children or family.

- Students, either full- or part-time, make up another seven percent of those living in poverty.

- Just three percent of those living in poverty are working-age adults who do not fall into one of these categories—that is, they are not in the labor force, not disabled, and not a student, caregiver, or retired.

- Five stereotypes about poor families and education, excerpt from Reaching and Teaching Students in Poverty: Strategies for Erasing the Opportunity Gap, Paul C. Gorski

Stereotype 2: Poor People Are Lazy

Another common stereotype about poor people, and particularly poor people of color (Cleaveland, 2008; Seccombe, 2002), is that they are lazy or have weak work ethics (Kelly, 2010). Unfortunately, despite its inaccuracy, the “laziness” image of people in poverty and the stigma attached to it has particularly devastating effects on the morale of poor communities (Cleaveland, 2008).

The truth is, there is no indication that poor people are lazier or have weaker work ethics than people from other socioeconomic groups (Iversen & Farber, 1996; Wilson, 1997). To the contrary, all indications are that poor people work just as hard as, and perhaps harder than, people from higher socioeconomic brackets (Reamer, Waldron, Hatcher, & Hayes, 2008). In fact, poor working adults work, on average, 2,500 hours per year, the rough equivalent of 1.2 full time jobs (Waldron, Roberts, & Reamer, 2004), often patching together several part-time jobs in order to support their families. People living in poverty who are working part-time are more likely than people from other socioeconomic conditions to be doing so involuntarily, despite seeking full-time work (Kim, 1999).

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.