Larry Cuban on School Reform and Classroom Practice: A Puzzling Question About Teaching in U.S. Schools

I like puzzling questions. Answers to such questions often go beyond yes/no or true/false. Moreover, answers often contain the seeds of further queries that complicate previous answers. Such is the case with the following question that has trailed me through my years as a high school history teacher, district superintendent, and university researcher:

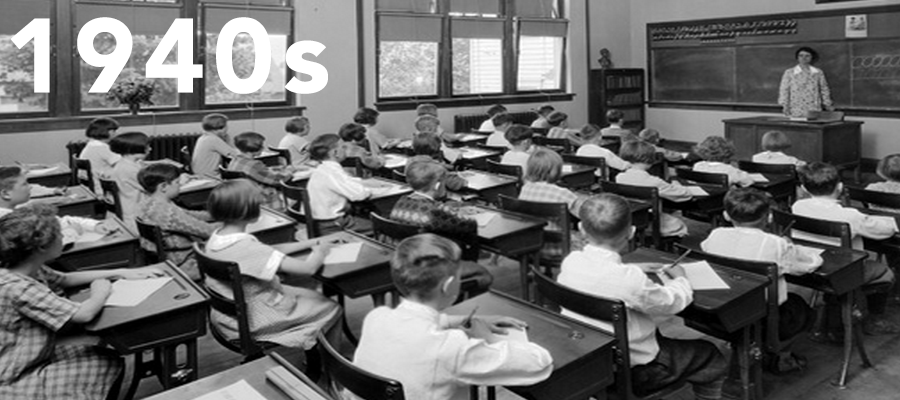

Why has the act of teaching in public schools (including charters) that serve wealthy, middle-class and poor children looked so familiar to past generations of journalists, researchers, parents and grandparents who observe classrooms?

Surely, things have changed in classrooms. Desktops and laptops are prevalent in schools; teachers use the Internet for videos in lessons; students give PowerPoint presentations; teachers take immediate polls of student answers to multiple choice questions with clickers; teachers use new textbooks, some of which are online.

Yet amid those classroom changes, there is a certain familiarity to past and present generations in how teachers unfold lessons, direct students to varied activities, ask query students that characterizes the common back-and-forth exchanges between teacher and students. How to explain that familiar continuity in teaching?

One way to explain this familiarity is the organizational concept of “dynamic conservatism.” This concept embraces both continuity and change in classrooms and schools. Institutions often change in order to remain the same. Families, hospitals, companies, courts, city and state bureaucracies, and the military frequently respond to major reforms by adopting those parts of changes that will sustain stability in their organizations. And so do teachers in their classrooms.[i]

Consider that more and more teachers provide carts with devices in their classrooms or urge students to bring their laptops to class to do Internet searches, take notes, and work in teams to make PowerPoint presentations to class. These teachers have made changes in how they teach while maintaining classroom discipline and managing the flow of activities in lessons. They “hugged the middle” between traditional and non-traditional ways of teaching.

Many academics joined with federal, state, and district policymakers who have seldom taught in K-12 schools remain dead-set on redesigning both school and classroom practices. Institutional stability is dysfunctional, they argue. They want transformation, not a few cosmetic changes. Such academics and policymakers see schools as complicated organizations that need a good dose of castor-oil rationality where both incentives and fear, not habits from a bygone era, drive employees to do the right thing in schools and classrooms. [ii]

When reform-minded policymakers intent on improving schools see classrooms as complicated rather than complex systems, hurdles multiply quickly to frustrate converting reforms into practice. Too many decision-makers lack understanding of “dynamic conservatism” in complex organizations such as classrooms; they choose to ignore it because they see these systems as ineffective and in need of re-engineering.

Recall previous efforts to jolt schools and classrooms sufficiently to substantially alter teaching and learning when academic cheerleaders and policymakers have mistakenly grafted practices borrowed from business organizations onto schools (e.g., zero-based budgeting in the 1970s; “management by objectives” and “restructuring schools” in the 1980s; pay-for-performance in the 1990s and loosening credential requirements for teachers since). They have ignored how teachers have habitually altered their classroom practices in order to maintain stability.

Analyzing the idea of “dynamic conservatism” at work in complex systems leads to a deeper understanding of why teaching over the past century has been a mix of old and new, mirroring both constancy and change. Change occurs all the time in schools and classrooms but not at the scope, pace, and schedule reform-driven policymakers and academics embrace. Stability in how schools work and how teachers teach are imperatives also. In failing to understand “dynamic conservatism,” federal, state, and district decision-makers who distribute funds and make rules governing schools too often repeat mistakes that earlier well-intentioned reformers made in seeking to alter daily teaching practices. Conflicts inevitably arise in schools and classrooms when policymakers fail to understand “dynamic conservatism” as a mainstay of public schools.

____________________________________

[i] Donald Schon, Beyond the Stable State: Public and Private Learning in a Changing Society (New York: Norton, 1973). See Larry Cuban, Hugging the Middle: How Teachers Teach in an Era of Testing and Accountability (New York: Teachers College Press, 2009).

[ii] John Chubb and Terry Moe, Politics, Markets, and America’s Schools (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1990). Frederick Hess, Spinning Wheels: The Politics of Urban School Reform (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1999).

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.