Larry Cuban on School Reform and Classroom Practice: From the Bottom Up: Teachers as Reformers

So easy to forget that teachers have changed how they have taught in their classrooms.

So easy to forget that in the age-graded school, teachers have discretion to decide what they will do in organizing the classroom, teaching the curriculum, and encouraging student participation.

So easy to forget that once teachers close their classroom doors, they put their thumbprints upon any top-down policy they are expected to put into practice.

In the constant drumroll of criticism that teachers and schools are stuck in the Ice Age and have hardly changed, the facts of teacher autonomy and incremental change are often forgotten in a state’s or district’s pell-mell rush to embrace the reform du jour. Historically there is much evidence that teachers –essentially conservative in their disposition– have changed (and do alter) classroom routines bit-by-bit including both the format and content of lessons even within the straitjacket of the age-graded school (see here and here).

Over time, in response to personal, community, and social concerns, most teachers add to or delete from the content and skills they are expected to teach. Additionally, they try out ideas that colleagues have suggested, a principal recommended, or ones that have come from their reading or that they saw in someone else’s classroom or heard at a conference. The classroom has been a venue for teachers’ steady change over the past century.

And so too has the school been an arena for incremental change often mirroring changes in the local community and larger society. Groups of teachers anxious about deteriorating discipline in their building, for example, approach their principal with a draft plan for the entire faculty to put into practice. Collaboration among teachers and with the principal emerge as a few teachers decide to pilot a piece of free software in behavioral management of their students. Some teachers form a reading group to explore a particular teaching innovation they have heard about. Of course, politically astute principals identify teacher leaders in their school and persuade them to investigate a school-wide change that she believes will help the school improve (see here, here, and here).

Both the classroom and school as venues for steady change can be the beginning of what I and others have called bottom-up reform, that is, changes bubbling to the surface with district leaders embracing the initiatives crafted in classrooms and schools and adopting changes in practice as new policies. Bottom-up is the opposite of top-down policies authorized by those federal, state, and local officials who make decisions.

Every U.S. and international reader of this blog knows what top-down change is. Even in a decentralized system of schooling in the U.S. with 50 states, 13,000-plus districts, over 100,000 schools, three and a half million teachers, and over 50 million students, most policies aimed at classrooms–new curriculum standards, taking standardized tests, buying brand-new laptops and tablets–come from federal, state, and district policies. Top-down not bottom-up policymaking has been the rule.

In acknowledging the rule, however, it is wise for policymakers and practitioners to recognize and remember that classrooms and schools are also crucibles for smart changes tailored to students in the here and now. Putting policies into practice is the teacher’s job. Teachers are the gatekeepers who determine which policies or parts of policies get implemented, a fact that too many decision-makers fail to get.

Historically, then, there have occasional bottom-up changes originating in classrooms and schools–often affected by external events–that have trickled upward to inform district and state policymakers. But most classroom changes stay localized in a particular school or network of schools rather than spreading across the educational landscape.

A few examples of teacher-led changes, however, come to mind.

Consider the “interactive student notebook” developed by a few San Francisco Bay area teachers in the 1970s and 1980s that has spread into many U.S. classrooms. When I entered “interactive student notebook” in a Google search I got over 35,500,000 hits (January 15, 2022).

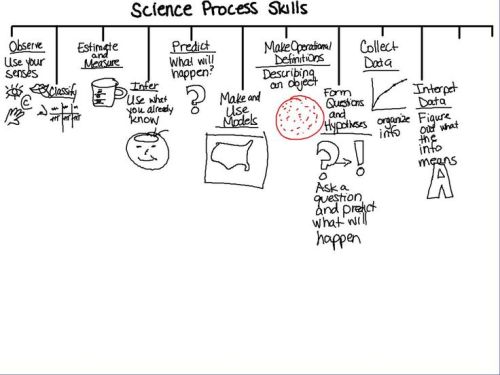

The over-riding purpose of ISNs is to have students organize information and concepts coming from the teacher, text, and software and creatively record all of it within a spiral notebook in order to analyze and understand at a deeper level what the information means and its applications to life.

In an ISN, students write on the right-hand page of a notebook with different colored pens and pencils information gotten from teacher lectures, textbooks, videos, readings, photos, and software. What is written could be the familiar notes taken from a teacher lecture or the requirements of doing a book report or the steps taken when scientists inquire into questions. These facts and concepts can be illustrated or simply jotted down.

The left-hand page is for the student to draw a picture, compose a song, make a cartoon, write a poem, or simply record emotions about the content they recorded on the right-hand page.

The ISN combines familiar information processing with opportunities for students to be creative in not only grasping facts and concepts but also by inventing and imagining other representations of the ideas. Both pages come into play (the following illustrations come from teachers and their students’ ISNs that have been posted on the web.

A student studying pre-Civil War politics over slavery put this on the right-hand page.

A student taking science put this on the right-hand page.

And for the left-hand side, a student studying North American explorers did this one:

And another student drawing and diagram for the road to colonial independence in

America on the left-hand side looked like this:

Origins of ISNs

While there may be other teachers who came up with the idea and developed it for their classes, one teacher in particular I do know embarked on such a journey and produced an interactive student notebook for his classes. Meet Lee Swenson.

A rural Minnesotan who graduated from Philips Exeter Academy and then Stanford University (with a major in history), Swenson went on to get his masters and teaching credential in a one-year program at Stanford. He applied for a social studies position in 1967 at Aragon High School in San Mateo (CA). Swenson retired from Aragon in 2005.

Beginning in the mid-1970s and extending through the 1980s, Swenson, an avid reader of both research and practice, tried out different ways of getting students to take notes on lectures and discussion, and write coherent, crisp essays for his World Study and U.S. history classes. He worked closely with his department chair Don Hill in coming up with ways that students could better organize and remember information that they got from lectures, textbooks, other readings, and films and portray that information in thoughtful, creative ways in their notebooks. They wanted to combine the verbal with the visual in ways that students would find helpful while encouraging students to be creative. Better student writing was part of their motivation in helping students organize and display what they have learned. Swenson and Hill took Bay Area Writing Project seminars. Swenson made presentations on helping students write through pre-writing exercises, using metaphors, and other techniques. It was a slow, zig-zag course in developing the ISN with many cul-de-sacs and stumbles.*

Both he and Don Hill began trying out in their history classes early renditions of what would eventually become ISNs by the late-1980s. In each version of ISN’s Swenson learned from errors he made, student suggestions, and comments from other teachers in the social studies and English departments in the school. Swenson made presentations at Aragon to science, English, and other departments, schools in the district, and social studies conferences in California and elsewhere.

By the mid-1990s, Swenson had developed a simplified model ISN that he and a small group of teachers inside and outside the district were using. The model continued to be a work in progress as teachers tweaked and adapted the ISN to their settings. By the end of that decade, a teacher at Aragon that Swenson knew joined a group of teachers at the Teacher Curriculum Institute who were creating a new history textbook.

Teachers Bert Bower and Jim Lobdell, founders of TCI, were heavily influenced by the work of Stanford University sociologist Elizabeth Cohen on small group collaboration and Harvard University’s cognitive psychologist Howard Gardner’s multiple intelligences. They wanted a new history text that would have powerful teaching strategies that called for student-teacher interactions. They hired that Aragon teacher who had worked with Swenson to join them; the teacher introduced them to the ISN that was in full bloom within Aragon’s social studies department. They saw the technique fitting closely to the framework they wanted in their new history textbook. TCI contacted Swenson and he became a co-author with Bower and Lobdell for the first and second editions of History Alive (1994 and 1998).

By 2017, TCI had online and print social studies (and science) textbooks for elementary, middle, and high school classrooms. One of the many features of the social studies books was “[T]he Interactive Student Notebook [that] challenges students with writing and drawing activities.” On their website, TCI asserts that their materials are in 5,000 school districts (there are 13,000-plus in the nation), 50, 000 schools (there are over 100,000 schools in the U.S.), 200,000 teachers (over 3.5 million in the country), and 4.5 million students (U.S. schools have over 50 million students).

From teacher Lee Swenson and colleagues’ slow unfolding of the idea of an interactive student notebook in the 1970s in one high school, the idea and practice of ISNs has spread and has taken hold as a technique that tens of thousands of teachers across the country include in their repertoire. Classroom change from the bottom up, not the top-down.

.

__________________________________

*Lee Swenson and I have known each other since the mid-1980s. As an Aragon teacher, he attended workshops sponsored by the Stanford/Schools Collaborative. In 1990, Swenson and I began team-teaching a social studies curriculum and instruction course in Stanford University’s Secondary Teacher Education Program. We taught that course for a decade. Since then we have stayed in touch through lunches, dinners, long conversations on bike rides, and occasional glasses of wine. He has shared with me his experiences and written materials in how he and Don Hill developed ISNs for their courses.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.