No End to Magical Thinking When It Comes to High-Tech Schooling

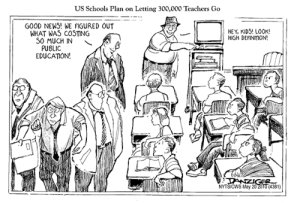

Few high-tech entrepreneurs, pundits, or booster of online learning, much less, policymakers, would ever say aloud publicly that robots and hand-held devices will eventually replace teachers. Yet many fantasize that such an outcome will occur. High-profile awards to entrepreneurs, the occasional cartoon, and advocates who dream of online instruction anywhere, anytime transforming education feed the fantasy.

Consider Sugata Mitra, Professor of Educational Technology at Newcastle University (United Kingdom). He recently received the TED award of $1 million for creating learning environments where illiterate Indian children had access to computers in actual holes-in-walls on streets of New Delhi slums. Some of the children told him: “You’ve given us a machine that works only in English, so we had to teach ourselves English.” Believing that children’s sense of wonder and intrepid curiosity would spur them to use computers and learn English, science, and whatever else they were curious about on their own, Mitra said to his audiences and funders: “My wish is to help design the future of learning by supporting children all over the world to tap into their innate sense of wonder and work together. Help me build the School in the Cloud, a learning lab in India, where children can embark on intellectual adventures by engaging and connecting with information and mentoring online.”

The million dollar award is not an accident when so many vendors, enthusiasts, and dreamers are willing to spend large sums of money to advance the spread of Mitra’s initiative and similar ones through both the developing and developed world.

More magical thinking–another noble dream–occurred nearly a decade ago with the One-Laptop-Per-Child initiative (OLPC). Nicholas Negroponte, MIT professor and former director of the MIT Media Lab, designed the project to put inexpensive, solar-powered laptops (running now around $200) in the hands of children and youth in least developed countries in Africa, Asia, and South America.

No shortage of critics, however.

Thus far, the largest distribution of laptops, nearly a million, have gone to rural and poor children in Peru over the past few years. A recent evaluation of the effort concluded:

*The program dramatically increased access to computers

*No evidence that the program increased learning in Math or Language.

*Some benefits on cognitive skills

Results for other developing countries such as Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Uruguay have similar mixed results. At best, it is too early to say what the benefits have been; after all, laptops are slowly becoming obsolete since smart phones and cheaper devices have nearly replaced them in many parts of the world; at worst, OLPC approaches what Mike Trucano, ICT specialist for the World Bank, listed as one of the 9 worst ed tech practices in the developing world: Dump hardware in schools, hope for magic to happen.

I certainly saw that with instructional television in the 1960s, desktop computers and labs in the 1980s, 1:1 laptop programs since the mid-1990s and I now see a similar pattern with iPads, other tablets, and smart phones. Magical thinking about transforming teaching and learning–dumping teachers and traditional schools disappearing–is close to make-believe even when children have these powerful devices in their hands.

Vendor-driven hype and wishful policy thinking over robots, increasingly sophisticated artificial intelligence software, and expanded virtual teaching feed private and public fantasies about replacing teachers and schools. Taking a step back and thinking about what parents, voters, and taxpayers want from schools–the social, economic, political, and individual goals–makes magical thinking more of a curse in the inevitable public disappointment and cynicism that ensue after money is spent, paltry results emerge, and machines become obsolete.

I end with the obvious point that magical thinking and the accompanying curse afflicts not only educators but also the rest of us, as these homeowners found out:

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.