The Past Lives on in the Present: Customized Learning Then and Now

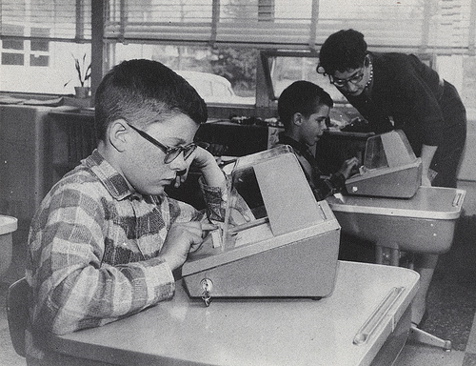

Pupils are working on their own. The second and third grade reading class of 63 pupils … is using a learning center and two adjoining rooms. Two teachers and the school librarian act as coordinators and tutors as the pupils proceed with the various materials prepared by the school’s teachers and … developer, The Learning and Research Development Center at the U. of Pittsburgh. Each pupil sets his own pace. He is listening to records and completing workbooks. When he has completed a unit of work, he is tested, the test is corrected immediately, and if he gets a grade of 85% or better he moves on. if not, the teacher offers a series of alternative activities to correct the weakness, including individual tutoring, There are no textbooks. There is virtually no lecturing by the teacher to the class as a whole. Instead, she is busy observing the child’s progress, evaluating his tests, writing prescriptions, and instructing individually or in small groups of pupils who need help.*

The school is Oakleaf elementary near Pittsburgh (PA) and the time is 1965. Implemented across all grades, the innovative program was called Individually Prescribed Instruction or IPI (el_197203_tillman-2, p. 495).

Nearly a half-century ago, before there were desktop computers, university developers and school-site practitioners championed IPI as a program where students move through materials at differentiated paces until each achieved mastery of the content and skills to then continue on to the next unit of study. Observers found students engaged in the process, pleased with the prompt feedback, and delighted that each could move at his or her pace rather than wait for the entire class to move to the next lesson.

Sound familiar?

It should. IPI was a more sophisticated version of psychologist B.F. Skinner’s “teaching machine” in the 1950s that evolved from “programmed learning” engineered by psychologist Sidney Pressey in the 1920s.

IPI was a prototype for subsequent online learning once electronic devices became widespread in K-12 and higher education. The DNA of present-day blended learning (e.g., Rocketship schools’ Learning Labs, Carpe Diem schools) and MOOCs in higher education reaches back nearly a century into “programmed learning,” “teaching machines,” and IPI.

Alright, Larry, you made the self-evident point that earlier renditions of self-paced, individualized learning appeared nearly a century ago. So what?

At that time and now, those various incarnations of individualized, self-paced learning sprang from competing ideologies of what children and youth should learn and how they should learn it. Student-centered vs. teacher-centered ways of teaching and learning (and mixes of both) have competed for time and space in K-12 schools for the past two centuries in schools. Teacher-centered instruction (e.g., lecture, discussion, textbook, worksheets, quizzes and tests) has won time and again and dominates classroom lessons. Yet student-centered instruction challenged conventional practice repeatedly.

Connecting students to the real world, students working in small groups and individually, teachers acting as guides and mentors, and a host of other student-centered activities that blend different subjects and skills (e.g., math, science, art, and poetry) moved to center stage of public attention on different occasions (e.g., progressive curriculum and instruction in the 1920s; open classrooms in late-1960s). But after a brief fling in the spotlight receded to the wings in past decades. Of course, there have been hybrids of both where many teachers hug the middle of the spectrum of instruction, but advocates for each pedagogical ideology continue to contest one another even today when K-12 battles erupt over different kinds of math content, reading textbooks, and early childhood programs.

In higher education, rival ideas about teaching and learning, albeit under wraps, drive different versions of MOOCs. The answer, then, to my “so what” question is that pedagogical ideologies that drove earlier versions of individualized, self-paced instruction are active in current versions of MOOCs.

The prevailing version of MOOCs offers traditional, technology-enriched teacher-centered instruction, that is, lecturing to large groups of people, asking occasional questions, online discussion sections, and multiple-choice questions on exams. Such MOOCs possess advantages of efficiency in delivering information especially in particular subjects (e.g. procedural knowledge in computer science, mathematics). Computer science departments at Stanford, MIT, and Harvard launched the initial MOOC offerings, not the Humanities, social sciences, or natural sciences, according to Keith Devlin, a Stanford University mathematician currently teaching a MOOC course on mathematical thinking.

There are other ways of teaching these courses, however. Some enthusiasts for MOOCs see opportunities for non-traditional forms of teaching where students learn from one another, form online communities, crowd-source answers to problems, create networks that distribute learning in ways that seldom occur in bricks-and-mortar colleges and universities. To Devlin, “the key to real learning has always been bi-directional human-human interaction (even better in some cases, multi-directional, multi-person interaction), not unidirectional instruction.” In other words, student-centered or learner-centered pedagogy.

So these rival ideologies contend with one another in MOOCs as they did when “teaching machines” and IPI were garnering public attention. Chances are efficiencies in cost and delivery will drive MOOCs toward teacher-centered instruction, as has occurred in the past. I would hope, however, that there would be attention to (and discussions of) MOOCs where benefits derived from student-centered ways of learning occur.

___________

*Thanks to Justin Reich and Dan Meyer for pointing me to IPI as a past reform that lives in the present.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.