Whither MOOCs?

Universal access to high-quality college courses at low cost for students anywhere with an Internet connection continues to make Massive Online Open Courses (MOOCs) the innovation that will, in the minds of its advocates, “revolutionize” or to use the favorite word of entrepreneurs, “disrupt” higher education.

Deep and abiding issues, however, prevent MOOCs from revolutionizing higher education. One issue is money. States have reduced funding for public higher education institutions. Universities have lowered labor costs by increasing adjunct and part-time faculty yet have raised tuition so that students face prices for going to college that far outstrip increases in wages and the cost of living. So how can MOOCs be converted into a revenue stream for money-strapped institutions? The other issue is the pattern of universities taming innovations to keep things as they are, a pattern that entrepreneurial reformers scorn and wish to overturn.

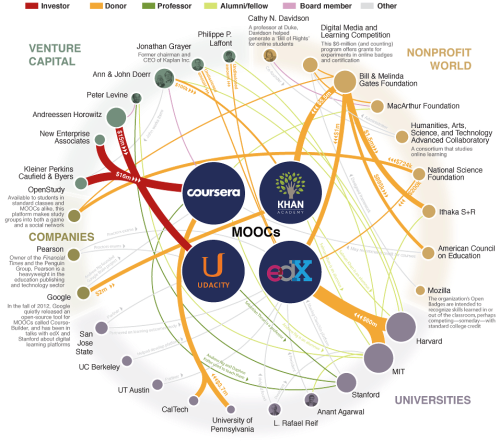

In the search for more students and more money, there have been a flock of start-ups in the emerging industry of MOOCs just as there have been among automobiles companies in early 20th century and telecommunications in late-20th century.

Of course, mortality rates run high in new industries as consolidation and new technologies come and go. Few remember car companies such as Packard or Hudson or, more recently the Hummer. In computers, what about Atari, Napster, Palm Computing, or Sun Microsystems? Or recall that Columbia University launched Fathom in the 1990s to promote online courses taught by its stellar faculty. Within a few years, Fathom sunk and was flushed, along with millions of dollars, down the toilet. As universities figure out how to make money from MOOCs–see efforts to have students pay for certificates, badges, and deals with universities where start-ups provide credit-bearing courses to students–the online industry will also shake out (as of last month, there are 28 providers of MOOCs internationally) with some of the current key players gone by 2020.

Why will some of these MOOC start-ups die? It is hard to make sufficient money year-after-year from delivering instruction because teaching and learning, unlike automobiles and washing machines, are not subject to productivity and efficiency gains.

Economists call this the “cost disease.” It applies to higher education and K-12. That is, in some kinds of labor-intensive work–nursing, social work, teaching, the performing arts–wages rise but productivity remains largely the same. Or as one economist put it: “While productivity gains have made it possible to assemble cars with only a tiny fraction of the labor that was once required, it still takes four musicians nine minutes to perform Beethoven’s String Quartet in C minor, just as it did in the 19th century.” Salaries for orchestra members increases over time but the quartet still plays Beethoven’s C minor piece in nine minutes. In a fit of humor, another economist made the same point about the “cost disease” phenomenon: With the possible exception of prostitution, teaching is the only profession that has had no productivity advance in the 2,400 years since Socrates taught the youth of Athens.

And so it is for K-12 teachers, professors, nurses, and other professionals in labor-intensive work. Efforts to stem the “cost disease” by measuring teachers’ performance based on test scores and linking results to salaries or tenure decisions on the basis of student evaluations of their professors’ instruction try to outflank the productivity issue but have failed to do so thus far.

Another reason MOOC start-ups will die is that colleges and universities tame innovations by incorporating aspects of the “newest thing” into existing structures and programs. Although critics would avoid the word “tame” in exchange for the word “co-opt,” the result is the same: institutions adopt changes to maintain continuity or what some academics call “dynamic conservatism” (see 1970_reith2-1). For MOOC entrepreneurs and those who seek to overhaul higher education, this strategy of maintaining institutional stability is both frustrating and wrong.

Consider the market-driven solution that Andrew Kelly and Frederick Hess propose (see Beyond Retrofitting-Innovation in Higher Ed).

…cheerful claims that American higher education is undergoing an irresistible change driven by digital technology are unduly optimistic. Technology has the potential to transform higher education as it has other knowledge-based sectors like music, journalism, and financial services, where new providers have unbundled goods and services and improved access and convenience while reducing costs. But technology does not guarantee innovation. Innovation demands that entrepreneurs use technology to re-engineer higher education.

The re-engineering that Kelly and Hess propose is to deregulate higher education (e.g., federal and state rules about accreditation of institutions, breaking up a college degree into pieces–”unbundling” as they put it–that students can re-assemble from different providers), focus on outcomes (e.g., what students learn, completion rates, success in job market) rather than spending time in classes for four years, and create a market where suppliers (e.g., for-profit and non-profit companies) compete for students who can assemble different pieces of learning from various companies. In short, Kelly and Hess want to deregulate higher education and create a competitive market where innovation will become omnipresent. And that is where MOOCs fit in, according to Kelly and Hess (June 24, 2013).

Advances in technology have made it possible to unpack a bundle of goods and services into their component parts and sell them separately, enabling customization and lowering of prices.

To transform higher education, issues of funding and universities taming innovation can be avoided if suppliers and consumers would operate within a market model. Retrofitting would be passe. Both the nation and students would benefit.

Which direction, then, for MOOCs?

Given the history of universities and colleges in the U.S., chances are that many higher education institutions (non-elite and community colleges) will continue to retrofit and transform MOOCs into credit-bearing courses that will yield revenue. MOOCs will not revolutionize higher education.

But higher education, already a collection of different markets serving different consumers, becoming deregulated and unbundled as Kelly and Hess propose is highly unlikely now and in the immediate future.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.