Larry Ferlazzo’s Websites of the Day...: What are the School Implications of New Chetty Study on Geographical Mobility?

Regular readers of this blog, and informed educators everywhere, know about the damage economist Raj Chetty has done to teachers, students, and schools by his exaggerated pronouncements about the education policy implications of his past work.

Today, he unveiled a new study that, as usual, has received lavish media attention. This one is very intriguing though, of course, his past work makes me a little wary of his conclusions in this one. It is difficult to be wary,, though, of such common sense results. Basically, he says that low-income children moving from poor neighborhoods to middle-income neighborhoods results in better life outcomes for the kids when they are adults.

Duh, you might say. Of course, living in areas with better-supported schools, less crime, and better community services would lead to more success for kids. Agreed. However, a previous study of much of the same data a few years ago did not find that to be the case. Chetty says his results are different because more years have passed and the positive outcomes took longer to become apparent.

Here are links to today’s articles on the study:

The New York Times has an article and an amazing interactive on the study.

Want to help poor kids? Help their parents move to a better neighborhood. is from Vox.

Where Poor Kids Grow Up Makes A Huge Difference is from NPR.

I’m wondering if the study’s conclusions, if accurate, might specifically apply to education policy discussions in two ways:

One, though I doubt it will, it would be great it would quiet those who push Social Emotional Learning as a “Let Them Eat Character” approach to responding to poverty instead of seeing SEL for what it is — if done well, a useful supplement to classroom instruction. Interestingly enough, the most public proponent of that mistaken and damaging perspective is New York Times columnist David Brooks, who pushed it again in a widely ridiculed weekend column. You can read more about this topic at my Washington Post column, The manipulation of Social Emotional Learning.

Despite what Brooks and other might say, escaping poverty is not just a problem of “psychology.”

Secondly, I wonder if it might not be a stretch to think this study says something about the damaging effects of classroom tracking by ability (see The Best Resources For Learning About Ability Grouping & Tracking)?

Plenty of studies have shown that students facing more challenges benefit more being in a mixed-ability classroom than in a lower-tracked one. The counter argument has been that some research shows that advanced learners do not gain similar benefits and are even hurt. However, as Carol Tomlinson has discussed, those studies showing a disadvantage for advanced learners have not been done in classrooms where teachers have been trained in differentiating up (she calls it a “plus-one” environment), as well as differentiating down.

As she writes:

The studies most cited in terms of benefits of homogeneous instruction for bright learners examined two conditions: heterogeneous classrooms in which little or nothing was done to provide plus-one learning for advanced learners, and homogeneous classrooms in which teachers regularly planned for plus-one learning.

In the two decades since those studies, I’ve observed and studied schools in which the entire faculty focused on providing a third condition: differentiation in mixed-ability classrooms where regular planning for a full spectrum of learners—including advanced learners—was a given.

It seems to me that a middle-class neighborhood with low-income families integrated within it is, in many ways, similar to the kind of classroom Tomlinson has observed — where, by force of numbers alone, a “plus-one” environment naturally occurs.

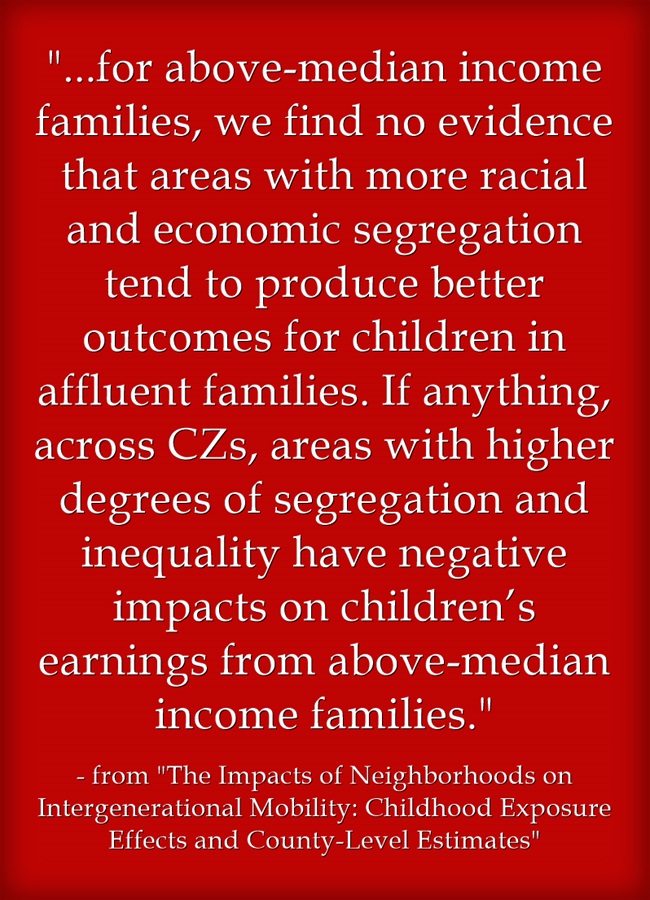

And, according to the Chetty study, what are the results of this kind of mixed-ability community for the young people who are in a more “advanced” position when families with more challenges move in?

(Thanks to Derek Thompson for bringing attention to that section of the Chetty study)

So, what do you think – am I as guilty of exaggerating the implications of this study as I have accused Chetty of being about his previous research?

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.