Larry Cuban on School Reform and Classroom Practice: Turning Around Urban Districts: The Case of Paul Vallas

Lee Iaccoca, Steve Jobs, and Ann Mulcahy were CEOs that resurrected Chrysler, Apple, and Xerox from near (or actual) bankruptcy to profitability. They were turnaround heroes–saviors, if you like–to their corporate boards and shareholders.

Salvaging a sinking business means that the CEO charts a new direction, outsiders arrive and veterans exit, novel products appear and old ones disappear–constant and unrelenting change is the order of the day in saving a company. A tough job that demands a thick skin with little time for regrets.

Turning around low-performing urban school districts is in the same class as CEOs turning around failing companies.

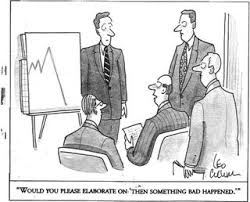

After serving in Chicago for six years, Philadelphia five years, and New Orleans four years, Paul Vallas put the saga of urban superintendents in stark, if not humorous, terms:

“What happens with turnaround superintendents is that the first two years you’re a demolitions expert. By the third year, if you get improvements, do school construction, and test scores go up, people start to think this isn’t so hard. By year four, people start to think you’re getting way too much credit. By year five, you’re chopped liver.”

Vallas’s operating principle, according to one journalist who covered his superintendency in Philadelphia, is: “Do things big, do them fast, and do them all at once.” For over a decade, the media christened Vallas as savior for each of the above three cities before exiting, but just last week, he stumbled in his fourth district–Bridgeport (CT) and ended up as “chopped liver” in less than two years.

Vallas is (or was) the premier “turnaround specialist.” Whether, indeed, Vallas turned around Chicago, Philadelphia, and New Orleans is contested. Supporters point to more charter schools, fresh faces in the classroom, new buildings, and slowly rising test scores; critics point to abysmal graduation rates for black and Latino students, enormous budget deficits, and implementation failures. After Bridgeport, however, his brand-name as a “turnaround specialist,” like “killer apps” of yore such as Lotus 1-2-3 and WordStar, may well fade.

Turning around a failing company or a school district is no work for sprinters, it is marathoners who refashion the company and district into successes. Lee Iaccoco was CEO of Chrysler from 1978-1992; Steve Jobs was CEO from 1997-2011, and Ann Mulcahy served 2001-2009.

Among big city superintendents, marathoners like Carl Cohn in Long Beach (CA), Pat Forgione in Austin (TX), and Tom Payzant in Boston (MA) took over failing districts and, serving over a decade in each place, built structures and leadership continuity that eventually earned awards for improved student achievement.

Superintendents with savior-like visions sprint through basket-case district for a few years and depart (e.g., Michelle Rhee in Washington, D.C., Rudy Crew in New York and Miami-Dade, Jean-Claude Brizard in Rochester and Chicago.

In many instances, sprinter superintendents follow a recipe: reorganize district administrators, take on teacher unions, and create new schools in their rush for better student achievement. They take dramatic and swift actions that will attract high media attention. But they also believe—here is where ideological myopia enters the picture—that low test scores and achievement gaps between whites and minorities are due in large part to reluctant (or inept) district bureaucrats, recalcitrant principals, and knuckle-dragging union leaders defending contracts that protect lousy teachers from pay-for-performance incentives.

Such beliefs, however, seriously misread why urban district students fail to reach proficiency levels and graduate high school. As important as it is to reorganize district offices, alter salary schedules, get rid of incompetent teachers and intractable principals, such actions in of themselves will not turn around a broken district. While there is both research and experiential evidence to support each of these beliefs as factors in hindering students’ academic performance, what undercuts sprinter-driven reforms in these arenas is the simple fact that fast-moving CEOs fast-track their solutions to these problems, get spent from there exertions or create too much turmoil, and soon exit leaving the debris of their reforms next to the skid marks in the parking lot. Swift actions certainly garner attention but sprinters quickly lose steam after completing 100 meters.

Consider long-distance runners. They carefully scrutinize and adapt reforms as they get implemented. Behind-the-scenes, they build teacher and administrator expertise to put changes into practice, mobilize staff and community to support long-term changes in teaching and learning, and, most important, create a pool of leaders ready to assume responsibility for sustaining the ever-shifting reform agenda.

They ask hard questions that few sprinter superintendents ask:

1. Did policies aimed at improving student achievement (e.g., small high schools, pay-for performance plans, new reading and math curricula, parental choice) get fully implemented?

2. When implemented fully, did they change the content and practice of teaching?

3. Did changed classroom practices account for what students learned?

4. Did what students learn achieve the goals set by policy makers?

Sprinter superintendents neither have the breathing capacity nor motivation to ask and answer these questions. They are too busy eyeing the finish line. Marathoners spend time and energy on these questions although 2 and 3 get skimpy attention from even the best of the long-distance runners. Still, urban children are better served by superintendents willing to go the distance rather than those swift runners who flash by without a backward glance.

Paul Vallas is (or was)* a sprinter at a time when marathoners are needed for turning around failing districts.

__________________

*A hearing on the removal of Vallas will occur in the Fall before the Connecticut Supreme Court

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.