Swiss Cheese Argument for School Reform: Add Another Hole

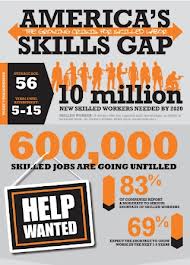

The prevailing rationale for school reform for the past thirty years, repeated by Presidents Ronald Reagan, George Herbert Walker Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama, is that there is a skills mismatch between what employers need in an information-based economy and graduates coming out of U.S. schools.

That lack of math, science, and technical skills among high school graduates means that employers cannot find job-seekers, just out of school or unemployed experienced workers, who can fill vacancies. Unfilled vacancies leave companies elsewhere grabbing a larger share of the market for goods and services that U.S. firms could produce. If schools would do their job of preparing skilled graduates, the three-decade old argument goes, then the economy would be stronger.

Politicians and policymakers focus on the skills mismatch because the problem can be fixed: more math, science, and technology in elementary and secondary in U.S. schools. In this way, students have the knowledge and skills to enter the labor market, get decent-paying jobs, and contribute to an ever-changing domestic and global economy. That unrelenting and unchallenged rationale for school reform, however, just developed another leak.*

Blaming schools for a skills mismatch is convenient and historical–remember that business and civic reformers pushed vocational education into U.S. schools over a century ago because of a so-called skills gap–but misses the central role that employers play in hiring new graduates and the unemployed.

According to University of Pennslyvania’s Peter Cappelli in his recent book Why Good People Can’t Get Jobs, the skills mismatch argument of the past thirty years is shot through with holes. Cappelli says:

There is no “mismatch” between the industries and occupations where people were laid off and where hiring is taking place…. Jobs have not changed over the last couple of years in any way that changed skill requirements substantially. The “failing schools” notion, even if it was true, couldn’t explain the continued unemployment of the majority of job seekers, who graduated years ago and had jobs just before the recession.

He emphasizes that employers are to blame, not schools. Yes, those who do the hiring. How can that be?

Cappelli has story after story of companies using complicated algorithms that screen out job seekers with requisite skills, paying low wages, and offering no on-the-job training. Employers, awash in applicants, don’t fill their vacancies and seldom calculate the opportunity costs of not filling the jobs.

Some examples:

*Employers only want experienced job seekers. The software many employers use screens out people who have the knowledge to do the job but have no experience or lack a perfect fit for jobs with narrowly drawn requirements. A firm advertises for an entry-level engineer and gets 25,000 responses. They couldn’t find the right engineer. Cappelli’s favorite example : the absurdity of this requirement was a job advertisement for a cotton candy machine operator – not a high-skill job – which required that applicants ‘demonstrate prior success in operating cotton candy machines.’ The most perverse manifestation of this approach is the many employers who now refuse to take applicants from unemployed candidates, the rationale being that their skills must be getting rusty.

In a labor market where employers have their pick of the crop, they shoot themselves in the foot by screening out able and qualified applicants.

*Not filling vacancies have costs that employers ignore:

Cappelli: If I were an employer, I would first begin… to ask if I know what it’s costing me to keep a vacancy open…. Do I know what it’s costing me to train somebody versus hiring somebody and chasing them on the outside? If you have answers to those questions, you start realizing that it does cost something to keep vacancies open. Searching forever for somebody — that purple squirrel, as they say in IT, that somebody who is so unique and so unusual, so perfect, although you never [find] them — that’s not a good idea.

Cappelli believes that employers need to loosen job requirements (and web-based software that screens out fine candidates) and offer paid internships and on-the-job training–as some employers still do.

There are already holes in the argument that high school graduates’ skills are mismatched to employer needs. Peter Cappelli adds another.

________

*Some historians have critiqued this reform-driven argument for linking the economy to better schooling. See Lawrence Cremin, Popular Education and Its Discontents (1989) Norton Grubb and Marvin Lazerson, The Education Gospel(2004), Larry Cuban, The Blackboard and the Bottom Line (2004), and David Labaree, Someone Has To Fail (2010). Also see posts here and here.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.