Sport Stats and Teacher Stats

“Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.”

Attributed to Albert Einstein

I just saw the film “Moneyball” which is about General Manager Billy Beane (played by Brad Pitt) whose Oakland Athletics shocked the baseball world in 2002 by nearly beating the New York Yankees in the American League playoffs. Why “shocked?” Because Beane had a player payroll costing $41 million and the Yankees laid out $126 million yet both won 103 games that season.

According to the book of the same name published in 2003, Beane upended the conventional wisdom of evaluating players and fielded a team of under-rated athletes that won 20 straight games in the 2002 season (an American League record) before meeting the Yankees in the playoffs.

How did he do it? Among baseball insiders, the conventional wisdom was to evaluate players for their potential by making subjective judgments that included numbers. For pitchers their throwing speed, repertoire of pitches, and control. For an infielder or outfielder, counting how many of the basic “tools” (e.g., hitting average, running speed, fielding skills) he had. When scouts found a tool-rich player, the Athletics developed him into a star player. Then–here’s the bad news–that star would skip to another team to earn more money. The Yankees, Red Sox, and Phillies had deeper pockets and often bought these rising stars and in the case of the Oakland team left them with a seriously depleted team in 2001.

Cut to a scene in the film where Beane is listening to his professional scouts discuss “tools” of various ballplayers they are considering for the 2002 season. He stops the discussion and tells them that traditional ways of evaluating ballplayers won’t work for the Athletics because in a small market like Oakland, they can’t pay top prices that big market teams could. Beane tells the scouts they must think differently about evaluating ballplayers and use different metrics such as how many times a player got on base rather than batting average. He tells them that a high-priced star is a blend of several talents so let’s look for less costly players who, together, combine those different talents into what the one super-star had. Using measures that few baseball insiders had applied, Beane and his high-tech side-kick tell these experienced scouts to identify under-valued players that met their new metrics. That is how Beane intended to build a new team for the 2002 season.

In this scene, scouts were upset that Beane ignored their wisdom gained from decades of experience. They knew which ballplayers were stars-in-the-rough; they didn’t have to listen to geeky analysts that Beane had hired to reel off percentages or see computer print-outs. Beane was rejecting their intuitions, experience, and “feel” for the game.

I must confess that this scene showing the confrontation between professional scouts touting their traditional ways of evaluating talent and the new “business plan” of using “sabermetric” principles reminded me, almost painfully, of the ongoing policy debates over evaluating degrees of teacher effectiveness. Why “painfully?”

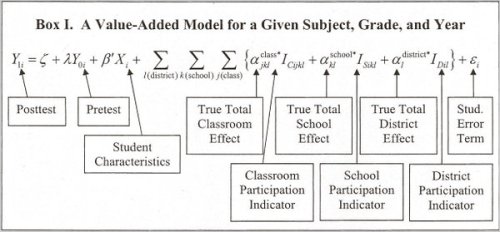

Professional scouts, based upon their experiences, intuitions, and insights into the game of baseball, made qualitative judgments (always including relevant statistics) about players. Just like many researchers, teachers, and administrators, I have argued against reducing the complexity of classroom teaching to an overall number, in part or wholly, based on students’ test scores to make judgments about effectiveness and salary. Long equations factoring in different aspects of teaching are now used in districts to evaluate teachers, get rid of under-performing ones while paying bonuses to effective ones–all determined by complex algorithms.

Caption as printed in the New York Times, March 7, 2011: A statistical model the New York City school system uses in calculating the effectiveness of teachers. In Michael Winerip’s column: http://tinyurl.com/4ssvkbz

My arguments–and here is where I winced during the film–reminded me of what I heard those professional scouts say as they protested Beane’s new metrics and hiring and firing decisions.

Many aspects of teaching (e.g., respect for students, teacher-student relationships, inspiring students to achieve) strongly linked to student behavior and performance cannot be easily captured by numbers. None appear in these algorithms. The above quote from Albert Einstein challenges the sabermetricbias.

Yet the current “business plan” for schools is to use a downsized version of educational “sabermetrics” for evaluating and paying teachers. In 2010, Washington, D.C., using algorithms to evaluate teachers, fired 241 teachers (about 4 percent of the district’s teacher corp) and put an additional 730 on notice that if they do not improve, they could be fired. Ditto for New Haven (CT) in 2010 where 75 of 1846 district teachers (just over 2 percent) were put on a list to be dismissed.

Oh, by the way, Billy Beane is still the Oakland’s A’s General Manager in 2011. His team made the American League playoffs in 2003 and 2006. Not once since then.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.