The Becoming Radical: The Real American Success Story

In the early 1990s after we had moved into our first stand-alone home (having lived in an owned townhouse a few years), my wife and I bought a Honda Accord—a typically American milestone of having finally risen above our station as Honda Civic owners.

As I was dong the paperwork for this car, I realized that the sale price was the same as what my parents had paid for their house in 1971 (a house, by the way, that still is more square footage than any house I have ever owned): $22,500.

I am one generation removed from the white working-class idealists who are my parents, both having been raised in the South during the 1950s—my mother the daughter of a mill worker and my father the son of a gas station owner.

Buying that Honda Accord, however, did not at that moment fill me with pride or a sense accomplishment. It made me feel extremely uncomfortable. I even called my father and told him about the coincidence of the prices of a car for me and the house my parents had worked themselves nearly to death to own.

My parents’ house sits on the largest lot of a local golf course, their having bought it as the course was being built and then scraped and clawed until they had the $1000 downpayment. Their monthly mortgage payment was also less than many of my car payments.

And while most people—especially my parents—would hold me up as proof of all that is Right with the U.S., I have to raise a hand of caution.

Yes, I have worked hard, but most of my success has come in academic settings—being a top student, and then working my way through undergraduate and graduate degrees while also having two careers, first as a high school teacher and now as a professor. To be perfectly blunt and honest, my success has been built on tremendous privilege—being white and male—and what appears to be hard work to many has in fact not been that hard for me at all.

Success in education depends a great deal on reading and writing—two behaviors that are for me both a joy and mostly easy to do.

#

In his Reaching and Teaching Students in Poverty, Paul C. Gorski notes “that many of us were raised to believe that the United States and its schools represent a meritocracy, wherein people achieve what they achieve based solely on their merit, so that all achievement is deserved rather than rendered” (pp. 14-15).

Historically, this American success story has been “tied to the Horatio Alger myth (Pascale, 2005) and the notions of rugged individualism and an ethic of self-sacrifice,” Gorski explains—what we often reduce to as “pulling ones self up by the bootstraps.”

However, this myth is nothing more than a twisted fairy tale—one that normalizes outliers and depends on a very ugly and false characterization of people in poverty: The impoverished, the subtext goes, create their poverty through their laziness.

The mostly false American success story keeps the accusatory gaze always on people in poverty so that little attention is paid to the larger forces of inequity in the U.S.

Gorski warns, “[M]ost of what poor people have in common has nothing to do with their culture or dispositions [ie., charges of laziness]. Instead, it has to do with what they experience, such as the bias and lack of access to basic needs” (p. 26).

#

Social forces—many of which are created and then perpetuated by privilege—drive conditions of scarcity (poverty) and slack (privilege) that are then reflected in the conditions surrounding and behaviors by individual people (see Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir’s Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much).

Therefore, we must confront the real American success story, the one that is typical of life in the U.S. and not one that misrepresents outliers as the expectations for everyone.

In the U.S., the floors of the penthouse of the wealthy are incredibly secure and stable, the few cracks are nearly as tight as they are rare. The best road to success in the U.S. is to be born wealthy.

As well, the ceilings on the basement of poverty are incredibly secure, allowing only a rare fortunate few through by superhuman efforts.

Instead of Horatio Alger, then, we must look to our own former president George W. Bush, who regularly joked about his C-student status, and whose SAT score both reflected a score higher than his GPA and fell below most of his peers accepted in Ivy League educations (an ironic two-fer that exposes the SAT as mostly a measure of wealth and privilege as well as showing how connectedness, being a legacy, is a privileged version of affirmative action).

George W. Bush has been very open as well about his struggle with alcoholism and his relatively unimpressive efforts at adulthood until he was nearly 40. Despite those hurdles and signs of laziness, he acquired part-ownership of the Texas Rangers and then became governor of Texas and president of the U.S.

I must, then, conclude that in the U.S., we have two Americas, and the one George W. Bush represents is the real American success story that exposes the key to achievement—not the content of ones character, but the coincidence of ones birth.

#

Writing in the New York Times, Susan Dynarski reports:

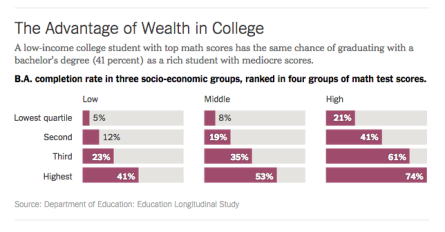

Rich and poor students don’t merely enroll in college at different rates; they also complete it at different rates. The graduation gap is even wider than the enrollment gap.

These sobering facts come from a longitudinal study and a connected report. And the data are stunning, but clear:

Source: Department of Education: Education Longitudinal Study

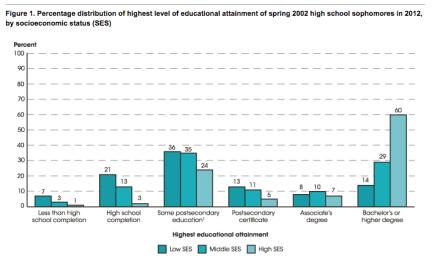

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Education Longitudinal Study of 2002 (ELS:2002), Base Year and Third Follow-up. See Digest of Education Statistics 2014, table 104.91.

Further, Dynarski continues, and then concludes:

Academic skills in high school, at least as measured by a standardized math test, explain only a small part of the socioeconomic gap in educational attainment.

Here’s another startling comparison: A poor teenager with top scores and a rich teenager with mediocre scores are equally likely to graduate with a bachelor’s degree. In both groups, 41 percent receive a degree by their late 20s.

And even among the affluent students with the lowest scores, 21 percent managed to receive a bachelor’s degree, compared with just 5 percent of the poorest students. Put bluntly, class trumps ability when it comes to college graduation.

Poor students are increasingly falling behind well-off children in their test scores, as recent research by Sean Reardon at Stanford University shows.

That is, any poor children who manage to score at the top of the class are increasingly beating the odds. Yet even when they beat the odds in high school, they still must fight a new set of tough odds when it comes to completing college.

#

Steph Curry has gained a well-deserved high level of recognition as the NBA League MYV in the 2014-2015 season. Like Grant Hill, Curry is the black son of a successful and wealthy professional athlete.

Curry is recognized as a hard worker—practicing at rates and amounts that most people cannot comprehend.

An ideal role model for black males in the U.S.?

Not according to high school English teacher Matt Amaral, who recently posted Dear Steph Curry, Now That You Are MVP Please Don’t Come Visit My High School and asked of Curry: “But I have to ask you to do me a solid and make sure you don’t ever come visit my high school.”

Amaral is making a concession I have argued above.

Curry is an outlier, and the personification of a potentially corrosive promise: You can be anything if you just work hard enough.

Well, no, that isn’t true.

So those of us who are parents and educators are put in a truly ugly position.

I love to inspire and encourage young people. I dearly and deeply love young people.

But I also cringe at the adult proclivity to lie in order not to face themselves the ugly truths they create and perpetuate—often by refusing to face them.

There is tremendous value in hard work and effort for the sake of hard work and effort.

And, yes, the world should be a meritocracy, the world should be fair.

Pretending it is while it isn’t, wrapping our young in shallow feel-good slogans and stories—these are sure ways never to achieve the equity we say we love in the U.S.

If we do not want to tell students the real American success story—the one about winning the birth lottery—we damn well better do something to create a better story instead of continuing to lie to children and ourselves.

Because, as you know, it is entirely within your power to make things different, right?

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.