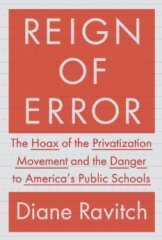

InterACT: Ravitch Seeks Broad Reforms to End Reign of Error

Just in time for its official release tomorrow, I’ve finished reading an advance copy of Diane Ravitch’s new book, Reign of Error: The Hoax of the Privatization Movement and the Danger to America’s Public Schools. For people who have been following education policy debates long enough and already know that they tend to agree with Diane Ravitch on most of the issues, there will not be any surprise revelations in the book; such readers might appreciate, as I did, Ravitch’s ability to pull together a combination of historical information, more recent studies, international comparisons, and various other sources that argue against the current direction of (supposed) education reform. For example, I didn’t know that the job protections commonly known as “tenure” actually pre-date teacher unionism (126). I was also interested to find some nuance in Ravitch’s argument against strict use of seniority, to the exclusion of other considerations based on students’ needs, in staffing decisions (130).

For those who tend to disagree with Ravitch on the issues, I would encourage them to take a look anyways, for two main reasons. The first is that, unlike recent books by purveyors of supposedly #RealEdTalk, Michelle Rhee and Steve Perry, Ravitch’s book minimizes personal narrative and substitutes copious footnotes and an index; in other words, she backs it up. You can disagree with her recommendations, but she makes it hard to deny the problems. Let’s take the chapter on charter schools for example. Ravitch points out the internal contradiction in charters claiming to be public schools when its time to collect money and win over politicians and voters, but claiming that they are exempt from many laws and regulations that apply to public schools. Cases that have gone to federal labor relations boards have held that the charters are essentially not public schools. You can argue otherwise if you want, but you should know those cases and what they say if you intend to engage on that topic. Ravitch’s book also details numerous examples of failed charters that rip off the taxpayers, shortchange students, hide the facts, and demonstrate all sorts of nepotism, conflicts of interest, and profiteering. These problems are almost inevitable under current laws; just like nature abhors a vacuum, individuals and companies tend to exploit available openings that help their bottom line. Ravitch’s conclusion is not, as you might expect, to ban charter schools, but rather to return to a system closer to the original vision of charter schools, putting in place a number of limits and controls that will remove the profit-making incentive, bring greater transparency, and provide genuine accountability to local entities. Charter school advocates may have a legitimate response in arguing that such limitations would undercut the idea of charters, but this book puts the ball in the charters’ court to honestly address some solutions to the rampant abuses in their midst.

Another eye-opener is Chapter 17, “Trouble in E-land” – showing how quickly we can move from a good idea to a tangled mess of lobbying and kickbacks. It’s apparent that direction of education change inclines towards technological integration, and there’s great appeal in expanding connectivity to allow all students similar opportunities to communicate, create, and access anything that will enhance their education. However, the content and technology providers, along with ALEC, are deep in the pockets of lawmakers now, writing favorable laws to be introduced by trusted legislators. The rapid expansion of virtual schools means a windfall for businesses and shareholders, but Ravitch cites numerous investigations that show much “education” spending is going towards overhead, lobbying, advertising, and the non-instruction of missing pupils. The results aren’t very good either, judged by standardized tests, and Ravitch notes the irony of virtual schools citing their students’ disproportionate poverty as the reason.

If you’re looking for a book that offers both sides of the argument in equal proportion, this isn’t it – nor is it meant to be. Reign of Error is a call to arms, advancing with clear intent a two-pronged argument, to pull us away from ineffective reforms and to present a better set of ideas. Perhaps it might win over more undecided readers, or soothe the feelings of those with opposing viewpoints, if Ravitch equivocated a little more often, credited more good intentions or cited the occasional successes of those lumped under the terms “reformers” or “privatizers” or “corporatists.” Maybe those individuals and groups aren’t conspiring to the degree Ravitch suggests – maybe not at all (but I doubt it). But when it comes to laying out the rampant problems in the dominant education reform agenda, Reign of Error is not a speculative work.

Ravitch states early on that much of her initial motivation to write the book was to answer a friend who wanted to hear some suggestions for improving education, rather than a litany of criticisms of education reform. These solutions constitute the second reason I’d recommend the book even to potential detractors. Though Ravitch spends more than half of the book exposing “the hoax,” the latter chapters arrives at concrete suggestions that would not only improve schools, but also others that would support children’s overall health and wellbeing in ways that would foster greater learning. Anyone who wants to knock Ravitch for not advocating solutions can’t really do that anymore.

What should we do to ensure strong public schools and a better education for American children? Here’s a partial list of Ravitch’s most concrete suggestions: ensure prenatal care for all pregnant women; provide high-quality early childhood education for all children; ensure a well-rounded curriculum, including the arts, civics, languages, and physical education; reduce class sizes; restrict charter schools to non-profit and non-chain status, promoting local collaboration and oversight; offer “wraparound” medical and social services; rely on higher quality assessment of students, and eliminate high-stakes standardized testing; elevate the teaching profession, and ensure that education leaders are professional educators; demand democratic control of public schools (as opposed to mayoral control, for example, or federal rules that impose a menu of punitive consequences as happened in Race to the Top).

Critics may argue that Ravitch’s proposals are too expensive or politically impossible, but in that case, where does the problem lie? How many studies and international comparisons does it take to convince education “reformers” that a concerted effort to confront poverty would be more productive than testing and performance pay? The negative effects of poverty on education are abundantly clear (see Ch. 10), while every favored “reform” strategy seems grounded in false assumptions and trailed by a string of failures (like failed performance pay schemes going back to the 19th century – see p. 117). Our national disregard for the overall wellbeing of other people’s children is a flimsy excuse for setting up a series of divisive debates on education policies that leave unmitigated so many fundamental inequities of greater import.

Professor Linda Darling-Hammond, Jan. 2012 (photo by the author)

Why not join together to fight the good fight, with a clear consensus? At one point Ravitch quotes Linda Darling-Hammond to make that point: Darling Hammond writes, “It’s not as though we don’t know what works. We could implement the policies that have reduced the achievement gap and transformed learning outcomes for students in high achieving nations where government policies largely prevent childhood poverty by guaranteeing housing, healthcare, and basic income security” (225). The same excerpt goes on to cite a number of effective economic and education reforms that peaked in the 1970s and early ’80s, having reduced the achievement gap significantly, and dramatically increasing college graduation rates; in 1975 there was parity in college attendance for whites, blacks, and Latinos, “for the first and only time before or since” (226).

So many of the narrow debates that derail us in American education reform efforts are really the byproduct of a refusal to address the greater problems requiring greater solutions. Since we’re unwilling to fight for transformative social supports that would fundamentally alter the life trajectories of millions of kids and families in poverty, we quarrel about the more smaller and more superficial elements. And the saddest part is that if “reformers” have their way, they still won’t get what they say they want. Schools won’t improve if we eliminate “tenure” and seniority, or if we put value-added measures into evaluations. Look around: those strategies haven’t worked yet, and no leading nations or school systems achieved greatness by those means. As Linda Darling-Hammond often says, “We can’t fire our way to Finland.”

In exposing the hoaxes and offering solutions, Diane Ravitch’s Reign of Error is on solid ground, cogent and well-supported, exposing widely divergent views of how to secure a viable future for kids and schools. For the past decade or more, we’ve tried blaming schools for their own neglect and injecting all sorts of policy and governance disruption into the education ecosystem. Most of that hasn’t worked, and maybe Ravitch’s book will help bring some people around to embracing a truly radical idea: start taking better care of children, families, communities, schools and teachers.

.

See my review of David Kirp’s Improbable Scholars to learn about another good book on American education reform.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.