Gary Rubinstein’s Blog: Open Letters to ‘B-List’ Reformers I Know. Part 3: Michael Petrilli

With social media, I suppose I can say that I ‘know’ someone if we’ve sent tweets to each other over the years. This is the case with Michael Petrilli. He is executive vice president of The Fordham Institute, and, according to his bio on their site, he is “one of the nation’s most trusted education analysts.”

I have been intrigued by ‘reform-minded’ Petrilli who, along with Rick Hess, occasionally writes something that admits the complexity of trying to improve education in this country. Most ‘reformers,’ particularly ones who are getting rich off of it, present such a caricature about what public schools and average teachers are supposedly doing and what charter schools and ‘highly effective’ teachers are supposedly doing. Petrilli, especially recently, has come out against some big ‘reform’ sacred cows. The most popular of these was a post called ‘College isn’t for everyone. Let’s stop pretending it is.‘ This caused Rishawn Biddle at Dropout Nation to write an article called ‘Mike Petrilli Gives Up On Reform.’

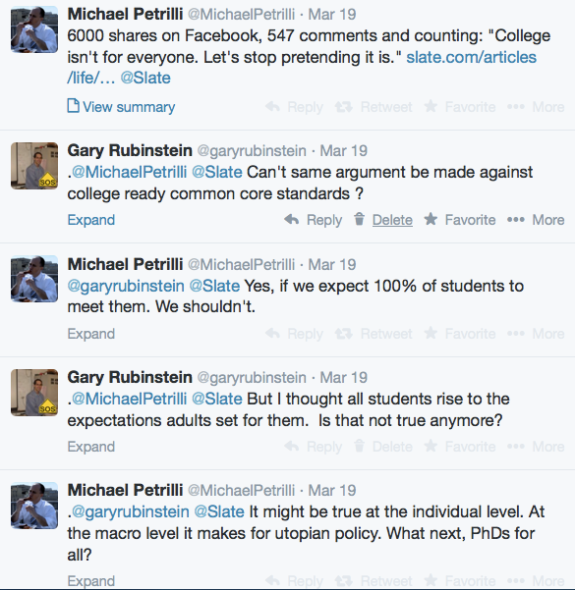

I ‘engaged’ with Petrilli on Twitter about his ‘College isn’t for everyone’ piece, and he wrote some things that would surely frustrate Biddle even more.

But despite Petrilli’s willingness to admit that improving education dramatically isn’t just about firing teachers and closing schools, Petrilli seems to have emerged as one of the nation’s leading cheerleaders of the Common Core Standards. He has been traveling around the country testifying in front of various legislatures and appearing on various news shows defending the Common Core from what he says is a small but vocal group.

I’m baffled by Petrilli’s ability to understand the counterarguments to some of the other ‘reform’ miracle cures yet to really seem unable to even validate the concerns many people, including many teachers, have about the Common Core. Instead he seems to deflect each of the pertinent questions with stuff he must know, deep down, are merely half-truths.

In this open letter, which I hope he responds to (I’m only two for twelve in responses!), I’ll try to be very specific about what I’d like him to address, and we’ll see if he does.

5/3/14

Dear Mike,

We’ve never met in person, but since I follow you on Twitter and since we’ve had some exchanges there, I hope you don’t mind being called a reformer I ‘know.’ The truth is that I don’t really know you since I am frequently confused by some inconsistencies in your writings.

The first piece that I read of yours that really struck me was a little over a year ago. It was called ‘Who Speaks For The Strivers’. Before this piece, the prevailing party line by reformers when charter schools were accused of serving a more motivated population — either by booting or counseling out low performers, or by having exclusionary admissions policies — they would say that this was not true. Charter schools had the ‘same kids’ as the local ‘failing’ school and their high test scores were proof that great teaching overcomes all. Your piece took a different approach. It said that, yes, charter schools were serving a more motivated population and that this is a good thing since those students deserve the opportunity to advance and not to be held back by their less motivated peers.

When I taught middle school during my first year, I thought about this a lot. If I could just find some way to silence the ten percent of students who seem to not care about learning, I reasoned, I can accomplish so much more with the other ninety percent. From a “greater good for the greater number” point of view, I can see the allure of that. I suppose that if the less motivated kids can be separated from the most motivated in a way that doesn’t help the high-achievers while simultaneously harming the low-achievers, maybe that would be some way to get test scores up in this country. I wish that more reformers would admit that this is what’s happening and admit, also, that they are OK with it. But most wouldn’t dare as it goes against the whole “Waiting For Superman” narrative that charter schools are working miracles with the ‘same kids’ thus proving that teacher’s unions are bad.

I, too, feel for ‘the strivers.’ I think the issue is that when the charter school says directly, or merely implies, that they serve the same populations as the nearby public school, and politicians believe this, it serves to harm the public school where the non-striver will be exiled to when it is determined that the student was not a ‘good fit’ for the charter school.

The next piece of yours that interested me was your review of ‘Reign Of Error.’ In the opening you made a very humble admission, “Fixing schools, especially from afar, is difficult, treacherous work, yet those of us in the reform community have tried to turn it into a morality play between good and evil. “We know what works, we just need the political will to do it,” goes the common refrain. Balderdash.” I do like that both you and Rick Hess are sometimes willing to call out ‘reformers’ for oversimplifying the issues or for being over-confident about their proposed solutions.

In your review you challenge six of Ravitch’s solutions. For two of them, lowering class size and increasing wrap around services, you point to research showing that these reforms don’t make a significant difference in student ‘achievement’ — as defined as standardized test scores. I’m a big proponent of lowering class size and increasing wrap around services, but not because I expect them to raise standardized test scores significantly. I think that these two reforms increase other metrics that don’t show up in the test scores. I know, as a teacher, that when I have 25 students in a class, I can give each student much more attention than when I have 34 in a class. I also get to know my students better in the smaller class setting. As far as wrap around services, I don’t care if they don’t increase test scores by much. They are important and humane and help kids and their families have better lives. You are right, though, that ‘reform’ hero Geoffrey Canada’s Harlem Children’s Zone schools have horrific test score results. When will ‘reformers’ start to demand that those schools get shut down?

But the most interesting writing I’ve seen from has come in the past few months starting with your controversial piece “College isn’t for everyone. Let’s stop pretending it is.” This got a lot of attention and caused Dropout Nation to basically call you a traitor. I saw this as a very important admission, one that you will not ever hear prominent ‘reformers’ admit to. For me, this gets to the heart of the education reform debate. ‘Reformers’ generally say that with ‘great teaching’ every student will get ‘college ready’ and then that student can choose whether or not he or she wants to go. In your article, you write:

Thus, in the reformers’ bible, the greatest sin is to look a student in the eye and say, “Kid, I’m sorry, but you’re just not college material.”

But what if such a cautionary sermon is exactly what some teenagers need? What if encouraging students to take a shot at the college track—despite very long odds of crossing its finish line—does them more harm than good?

This is a great question. I see it as you saying that there is a limit to what influence a school, no matter how good it is, can be expected to do. This is so important since the “Waiting For Superman” narrative, still echoed by Arne Duncan, is that there are many schools that are proving that schools actually are not limited in their influence. If teachers are just effective enough, 100% of the students will go to college. On my Twitter feed I always see Tweets from TFA or from Arne Duncan about this school or that one having 100% college acceptance. Always when I investigate these claims I learn that it was only 100% of the seniors. They conveniently leave out that nearly half the ninth graders who began at that school three years earlier left the school before becoming seniors.

You even wrote a thoughtful follow up last month called “‘College and career ready’ sounds great. But what about the kids who are neither?” In this piece, you responded to critics from your own camp:

Do Biddle and others really think we can ramp up the number of “prepared” ninth-grade students in big cities from 10 or 20 percent to 100 percent? I don’t, and I don’t think that means I must turn in my reform credentials. It just makes me realistic—and somewhat competent at math.

So I do think that you have the ability to go against the cliches of the ‘reformers’ to dig deeper and I do appreciate that.

But …….

Why do you seem to have such blind faith in the Common Core standards? You act like you can’t even understand, let alone dignify with a response, the main criticisms of them. There are a lot of issues with the standards. One is that they are not of a very high quality. Even when actual teachers try to develop new curriculum (yes, I’m aware that the standards aren’t officially a curriculum — but they kind of are. Don’t pretend you can’t understand how the two things are related), the first draft often has problems. There are things that sound good on paper, but when you actually TEST them, you find that they were bad for various reasons. And that is when a teacher is writing a curriculum for a specific class where the creator of the curriculum knows the audience quite well. So if you have a bunch of people who know little about teaching come together and attempt to ‘backward plan’ from an ambiguous ‘college ready’ definition and work all the way back to Kindergarten. And do this for an audience that is the entire country. It’s not gonna work.

So now that things are becoming messy, the big response is that the problem isn’t the Common Core, it’s the implementation. So do you know of any state that has had a good implementation so far? At some point, when every new and improved implementation fails, will you be willing to consider the possibility that maybe the reason it was so hard to implement was because it wasn’t a very good set of standards?

But this isn’t the biggest problem I have with the Common Core and the defending of it by you and even by Randi Weingarten. The problem I have, and this is one that I have not heard you address specifically, is that it is based on several shaky premises. The weakest premise, and one I really hope you’ll address, is that “raising standards” — making them harder, you can call it ‘rigor’ if you want to use a euphemism will “raise achievement.” Do you have any basis for that belief? I even saw in a recent thing you wrote,

For instance, the standards are clear that elementary-school teachers should assign texts that match a student’s grade level, rather than their current reading level. Yet the majority of teachers reported that they continue to assign such “leveled texts” to their charges.

Have you found that when you try to learn something that starting with an advanced level book on that topic helps you learn? Maybe you like to run on the treadmill. Try this, double the speed that you usually run at. See how that works out for you. I’ve taught for 16 of the past 23 years and my goal is to teach just a little bit beyond the student’s comfort level. When you try to push kids too hard, they get discouraged. This does not maximize learning. Even with things that I try to learn, like Chess and piano, if I try to read too hard of a Chess book or try to play a piano piece that is way above my level — it just doesn’t work. And I’m an adult who is choosing to study this stuff in my spare time, not a child who is forced to sit through a math class. Come on. This is common sense. Yet the opposite, the idea that making it harder is surely going to raise achievement, is the main premise of the argument of the common core.

Yes, I admit that there can be expectations that are too low, and that’s not good either. I see people at the gym on the treadmill and they’re reading the New Yorker at the same time, and I’m thinking if you’re able to comprehend ‘Shouts and Murmurs’ you’re not running fast enough. But I am not convinced that the old standards were too easy like that. In my experience with teachers and as a teacher, I find that it is to the teacher’s and to the student’s advantage for the teacher to teach at the appropriate level, not too hard, not too easy. This is because students get bored and misbehave when it is too easy and when it is too hard. The students, in a sense, train the teacher to teach to the proper level, and a federal mandate to teach faster and harder upsets this self-correcting feedback loop.

Did Alabama and Mississippi really have such low standards that it required a federal intervention? I seriously doubt it. We all use the same textbooks and teach the same sorts of things. Algebra I, Geometry, Algebra II, reading books, writing essays. What do you think all the educators in Mississippi have been doing for all these years before the common core? Surely kids from those states had to take the SATs and they were not completely bewildered by them so much more than kids from other states. I think the argument that the standards were so different before the common core is incredibly exaggerated.

The common core has been oversold as some necessary miracle cure. It isn’t a miracle. It isn’t going to cure anything. And it is very, very expensive. It was a waste of money, I think. Do you have some sort of estimate of the complete cost of the common core and the expected boost in achievement because of it. You, yourself, admit that schools are not able to perform miracles and get everyone ‘college ready’ so the expected boost can’t be so gigantic. Is it worth all that money?

That’s all I have in me about this right now. If you are willing to write back, I’d appreciate it.

Sincerely,

Gary

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.