Jersey Jazzman: New Report on the Consequences of Inadequately Funded Schools

Yesterday, the Education Law Center released a report they commissioned from yours truly about the consequences of inadequately funding school districts.

"Shortchanging New Jersey Students: How Inadequate Funding Has Led to Reduced Staff and Growing Disparities in the State’s Public Schools" is a look at how students are affected when the state refuses to meet its obligations and give schools the resources they need to succeed. As usual, I'll try to explain here, in layman's terms, what's going on in this report.

But first: many thanks to Dr. Danielle Farrie, Research Director at ELC, who was my collaborator on this report. Danielle was the one who calculated the adequacy rates for the districts we looked at, guided my thinking, and contributed much to the final text. And thanks also to Dr. Bruce Baker, who, as always, was an invaluable resource.

If there's a central issue in education funding today, it's "adequacy." A common mistake of those not deeply engaged in issues of education financing is to substitute "equity" for "adequacy" -- but they are not the same. Here's Bruce and Preston Green's explanation of the difference:

"Equity conceptions deal primarily with variations or relative differences in educational resources, processes, and outcomes across children, whereas adequacy conceptions attempt to address in more absolute terms, how much funding, how many resources, or what quality of educational outcomes are sufficient to meet state constitutional mandates."

This is a big, complicated topic, but maybe we can boil it down to this -- a famous cartoon I've edited:

Again, I'm way oversimplifying here ("equity" above should probably really be "horizontal equity," but that's a long discussion...), but the main point is this: adequacy has to do with whether or not a school district has what it needs to get the job done. In New Jersey, as in other states, there is a formula that the state uses to determine whether a district has enough funding: the School Funding Reform Act, or SFRA.

SFRA is predicated on the idea that you need to get more resources to students who need them more, in order to make sure all students have an "adequate" education (Don't get thrown by the word "adequate" -- it doesn't mean, in this context, "so-so" or "mediocre." A better synonym might be "sufficient.").

The state gives more aid to districts that need it based on the numbers of children who are "at-risk" (which we measure by whether they qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, a proxy measure for economic disadvantage), are Limited English Proficient, or have special education needs (emotional disabilities, cognitive disabilities, physical disabilities, speech impairments, autism, etc.). The premise -- supported by a ton of research -- is that these children cost more to educate because they need more individualized instruction and specialized programs. Makes sense, right?

Well, not to many politicians -- including Chris Christie. Under his reign, the number of districts that have not received adequate funding (and remember: the funding level is written into law) has skyrocketed. School districts across the state have been shortchanged about $4.5 billion since Christie took office. Here's a look at how many students have been affected:

Just about half of the public school students in New Jersey are in an inadequately funded school district. The "deeply inadequate" districts are those that are more than 20% under their adequacy targets, set by SFRA.

Now, the "money doesn't matter" crowd likes to pretend that this really isn't important. Somehow, all that extra money is being wasted and there's all this abuse and the schools that serve more of the children who need more resources have more than enough to get by. Never mind that many of the inadequately funded schools are in school districts that are relatively more affluent: if you look above, you'll see many "non-Abbott" districts -- the ones that have District Factor Group (DFG) of CD or higher -- actually don't get the funding that they need.

No, the argument goes, adequacy isn't nearly as important as things like teacher tenure. This is, of course, transparently absurd, but never mind: it has become the pseudo-intellectual cover under which politicians like Christie have ignored the law and underfunded schools.

Now, what we really haven't been able to do much until now (at least in New Jersey) is use data to see if there are specific consequences to underfunding schools. Yes, we can look at per pupil spending figures -- but what are the classroom-level consequences when you underfund a school district? What exactly changes in a child's school experience that can be traced back to inadequate funding?

This report is one attempt to find an answer. Here's what we did:

New Jersey tracks every certificated educator in the state in a yearly file that is based on data submitted by the individual schools districts. These staffing files give the name, salary, education, experience, race, and gender of everyone who works in a school and holds a New Jersey education certification.

These files also have a really important bit of info attached to each name: a job code, which tells us exactly what that person's function is within their school. I, for example, am listed as a "2100": "Music Comprehensive." This is very valuable, because we can get a good sense of the programs that are offered and the depth of those programs by comparing the "student load"-- the number of students per teacher -- for teachers in each department within a school district.

Imagine, for example, a district that had one music teacher for every 350 students, versus one for every 500 students. We'd be right to think that the district with more music teachers per student would have a richer music program with more course offerings, because the music teachers would be spread less thinly than the district with fewer music teachers per student. In other words: if I only have to teach 350 students, rather than 500, I'm going to be able to offer more music classroom time, a deeper music curriculum, and more course options.

So let's see how this works out. We'll start just by looking at the overall student-teacher ratios for districts that are adequately, inadequately, and deeply inadequately funded.

There are three things to notice here: first, the teachers in the inadequately funded districts had a greater student load than teachers in the adequately funded districts going back to just before Christie took office. In other words, the students in inadequately funded districts had fewer teachers working with them even before the cuts in state aid started.

Second: all students -- even those in adequately funded districts -- had fewer teachers by the time we got to the end of Christie's first term. The teacher load has increased across the board as the state has pulled back from full funding of SFRA.

Third, and perhaps most important: the student-teacher ratio gap between adequately and inadequately funded districts has increased during the Christie administration. As much as kids in adequately funded districts were getting left behind before Christie took office, things have become even worse.

(One caution: don't read this thinking it represents class sizes. We're talking all certificated staff here: principals, guidance counselors, nurses, speech therapists, etc. Many important people who work in schools aren't classroom teachers.)

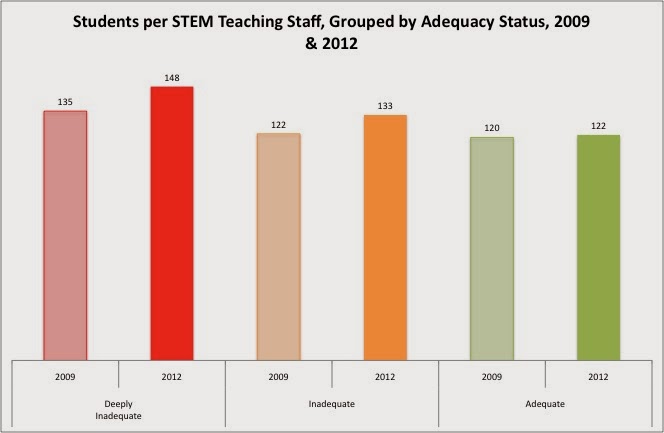

So, how does this affect specific programs and course offerings? Well, using the job codes, we can break out different types of educators, and see how their teaching loads have changed based on whether or not they are in an adequately or inadequately funded district. I have several examples in the report, but here's one I think is particularly instructive:

Everyone these days talks about STEM -- Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics -- education. According to the powers-that-be, it's the key to retaining our competitive edge over the rest of the world. But look at what's happened: New Jersey's inadequately funded districts were already behind on deploying more STEM teachers into their schools -- and the gap between them and adequately funded districts has grown worse. If you teach STEM in an adequately funded district, your student load has barely changed; not so if you teach in a deeply inadequately funded district.

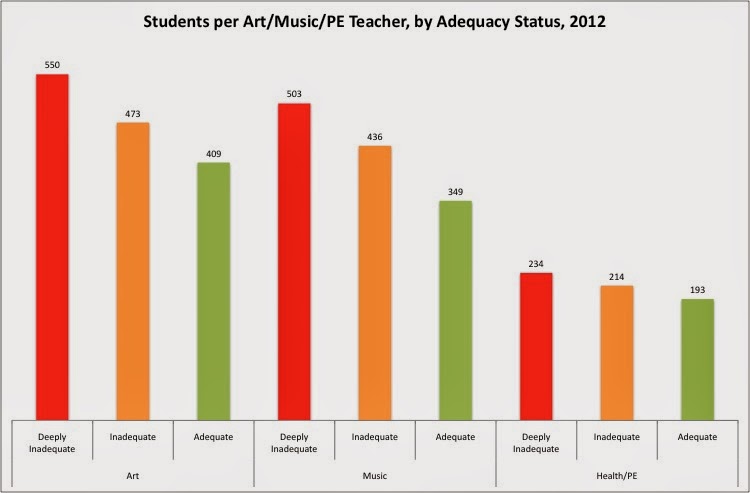

And it doesn't stop at STEM. Here's a look at the differences in student loads in curricular areas that are outside of the "core" subjects:

Art, music, and PE teachers in inadequately funded districts have significantly higher student loads than teachers in adequately funded districts. Think about that a bit as it relates to college admissions: don't the elite colleges look for well-rounded students who have significant experiences in the arts and athletics? Doesn't the kid who has an extensive sculpture portfolio stand a better chance of getting into an Ivy League school as a pre-med major than the one who doesn't, all other factors being equal? Don't more PE teachers likely translate into more coaches of interscholastic sports, which means more teams, more choices, and more chances to build up a college resume?

Here's another:

As I say in the report, elite colleges often require the study of a foreign languages as a pre-requiste for admission. Who has a better chance of studying a variety of languages and taking AP-level courses: a student in a district where each foreign language teacher averages a load of 425 students, or a load of 288?

As for the nurse and counselors: while inadequately funded districts are in all DFGs, the deeply inadequately funded districts tend to be the less-affluent ones. So we're stretching our counselors and school nurses thinner in the districts that have more students in economic disadvantage -- and those are the students who actually need those services the most.

As they say: read the whole thing. The takeaway is this: money really does matter. When you do not provide a school district with adequate resources, there are real and meaningful deficits in the education of that districts's students.

I understand that we have many priorities in this state, including the pensions, our infrastructure, property tax relief for the middle-class, and overall tax relief for the working poor. But adequate school funding has got to be a priority as well. Despite the denials of some, we can't give kids an adequate and equitable education until we start giving their schools the resources they need to get the job done.

Again, thanks to ELC for the opportunity to do this report. Undoubtedly, there will be more to come on this topic over the next year - stay tuned.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.