Living in Dialogue: High Stakes Testing Makes Surveillance Necessary

Pearson employees may be off for the weekend but when they get to work tomorrow they will find they have a big mess to deal with. The news broke on Friday that Pearson has been monitoring student social media, and has worked with District officials in several instances to ferret out and reprimand students who they Pearson feels have carried out an “item breach.” Pearson stated that the student had posted a photograph of a test item, but that part was untrue, according to the school official who raised concerns about this with her staff.

According to Bob Braun, his blog suffered a “denial of service” attack after the post was published, making it difficult to access. If that is true, someone with some powerful technical skills is working to defend Pearson’s reputation. But the site is back online now.

Here is Pearson’s official explanation of how it monitors social media.

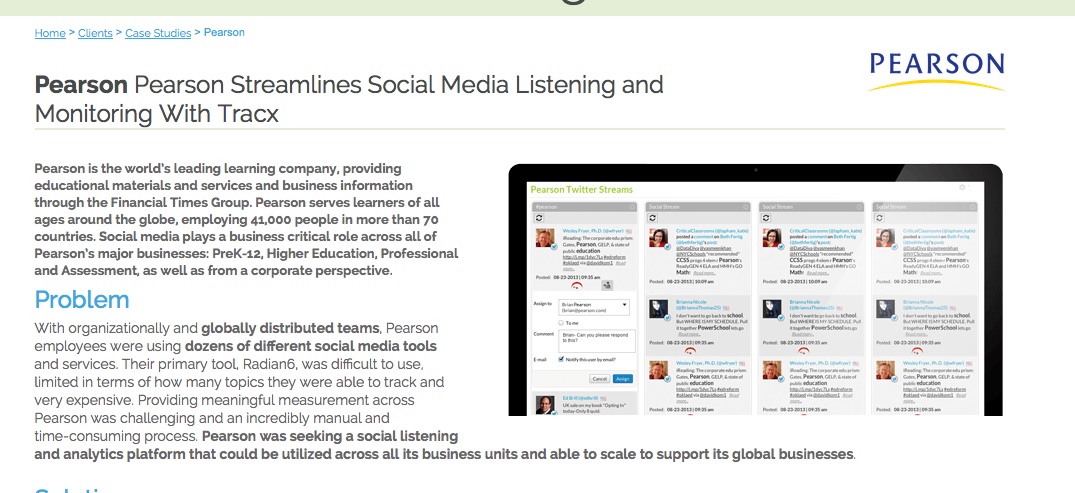

Pearson was also featured as a “case study” by one of the services they use, a company called TRACX. These folks were working over the weekend, because the page that showed the case has since been taken down. But not before I took a couple of screenshots, which show them monitoring activists like Wesley Fryer and Katie Lapham.

Another shoe dropped on the subject when Mercedes Schneider shared news that the SBAC test, in use in even more states than the Pearson tests, also has a social media monitoring system. Mercedes Schneider shares the full document here. Here is the SBAC’s suggestion to school district officials:

Sites to Monitor

Twitter (https://twitter.com/.) If your school has a Twitter account, you can take advantage of following your students by requesting their @username and/or encouraging them to the follow the school Twitter account.

- To search for conversations and posts about the Field Test, consider the following search queries: #sbac or #smarterbalanced; #[insert name of school] or @[insert school Twitter handle] and “smarter balanced” or “sbac”

Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/) If your school has a Facebook page, invite your students to join. If your students have public profiles, you can also search their news feed and photo gallery for security breaches.

- Similar to Twitter, you can conduct searches by entering “smarter balanced” or “sbac” or “[insert name of school]”

Statigram (statigram.com.) Statigram is a webviewer for Instagram and allows you to search and manage comments more easily. You will need to create an account for yourself to search comments on Statigram. If you have a private account, you can use this information to login and review information.

- To search for posts about the Field Test, use the same search queries recommended for Twitter.

Cynthia Liu at K12Network News had an interesting perspective, suggesting that we focus not on the “spying” aspect, but instead:

Pearson is not “spying” on student tweets, it’s enlisting public school officials — the New Jersey Department of Education — to defend its intellectual property. The latter is worse and a bigger problem.

She explains:

Push back on Pearson should be because this for-proft company is attempting to make principals and superintendents infringe on free speech rights of students in order to protect Pearson’s property interests, which is a corporate abuse of public school officials. And the NJ DOE is avidly assisting in this effort to pressure local school officials.

I think the issues are closely related.

By creating a state-sponsored “accountability” system that attaches heavy consequences to student performance on tests, the state and its corporate test-making partners have created a compelling need for extensive surveillance of everyone that accountability system touches. Teacher and administrator evaluations and thus jobs depend on these scores. Schools may be closed. Funding to schools is increased or reduced. And the tests are supposed to determine which students are ready for college.

All these consequences create reasons for people to game the system – and this has been the hallmark of NCLB from its inception. The “Texas Miracle” that inspired NCLB was based on the creative practice of holding back the 9th graders whose scores would make the schools look bad. Result? A miraculous rise in scores, a Texas governor who bragged he was an “education governor” on his way to the White House, and brought us a whole system of accountability based on test scores. And NCLB has made test-based accountability a part of the basic contract between the Federal government and the schools that receive federal funding.

Any system that imparts heavy consequences for success or failure must have intense security. How do you impose test security on a system that must test as many as fifty million school children every year, when many millions of these students have smart phones and Facebook accounts? You MUST have a surveillance apparatus. You must also have local District personnel act as your deputies in monitoring these activities, and in meting out consequences for those who violate your rules. It is all an inescapable outgrowth of creating a system that rewards and punishes people based on student test scores.

The Pearson guidelines make for a very fuzzy definition of the term “test security.” Bob Braun explains:

Here is what the State of New Jersey and Pearson agreed encompassed the idea of security and its possible breach–it’s codified in the testing manual developed by the state and sent out to all the districts:

“Revealing or discussing passages or test items with anyone, including students and school staff, through verbal exchange, email, social media, or any other form of communication.”

Another opportunity for repetition for emphasis here–discussing? Any other form of communication?

So, if children come home from school and their parents ask–”How was your day, sweetheart?” and the children talk about a really dumb question on the PARCC, they will be violating the rules and be subject to whatever punishment is meted out for cheating–as a blogger did who learned from a child who hadn’t taken the test that there was a passage on it about The Wizard of Oz.

This controversy comes in the midst of growing anxiety about the national “opt out” movement. Remember, it does not take a huge number of students opting out to render test results invalid. So if just five or ten percent of the students in a given school choose to opt out, then the system has been defeated.

Last week a school in Rhode Island suspended a teacher who simply discussed the PARCC test with his students.

As Cynthia Liu points out, this is all about Pearson (and SBAC) protecting the sanctity of their tests. These tests are highly vulnerable to social media. This morning, Diane Ravitch called on teachers and students to engage in civil disobedience.

The problem the test makers have encountered is a basic one, not easily fixed. Their systems depend on public credibility not only in the accuracy and reliability of their tests, but on their justice. If teachers and students felt these tests were an accurate reflection of learning, and were a useful means of measuring how well schools are doing their job, we would not have this crisis. But when these tests are the outgrowth of a discredited accountability system, and connected to Common Core standards that were largely imposed with little input from educators, parents or students, their credibility is weak. The system relies on teachers to administer the test, and to reinforce its legitimacy with students and parents. When teachers and parents have lost faith in the fairness of the tests, and actually see the tests as unfair and illegitimate, the system is in danger of collapsing.

Critics of those opting out have compared parents who opt their children out to parents who refuse to have their children vaccinated. However, while there is strong scientific evidence that vaccines save lives, there is zero evidence that the Common Core standards and these tests will improve the lives of our students. In fact, judging from states like New York that are on the leading edge, these tests are likely to have a very negative effect. Thus, those who opt out are the ones acting in the best interest of children.

What do you think? Is this sort of surveillance an inevitable outgrowth of high stakes testing? How should parents, teachers and students respond?

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.