The Becoming Radical: Beware the Roadbuilders Redux: Education Reform Wars Fail Race, Again

A classic analogy is Mothra vs. Godzilla, but a more contemporary comparison—and one to be highlighted in upcoming Marvel superhero films—is Marvel’s Civil Wars.

First, the larger situation involves two powerful forces, both of which are driven by the missionary zeal of being on the right side, that wage war against each other while those who both sides claim to serve is trampled beneath them as collateral, and mostly ignored, damage.

More specifically, Marvel’s Civil War involves two legions of superheroes (and villains) who side with either Iron Man or Captain America (the two powerful forces characterized by missionary zeal and reckless disregard for citizens), but notable in this war is that the X-Men are neutral, as is Black Panther—serving as embodiments in the comic book universe of the Other (identified groups marginalized by status: race, sexual/gender identities, poverty).

Finally, what does this template represent? I recommend reading carefully Andre Perry’s Education reform is working in New Orleans – just like white privilege—notably:

White critics of education reform should especially include themselves in the power structure. Yes, the neo-liberal, market-driven, corporate anti-reform critique isn’t the only frame that robs black people of their voice.

I wish white folk would hear me when I say the pro-/anti-reform frame doesn’t work for black folk. If anything, our position in the social world makes us reformers. Black folk never had the luxury of defending status quo. New Orleans needed to make radical changes in education as part of larger hurricane preparedness plan. Getting a college degree is the kind of protection black people need. Cynicism isn’t protection.

Perry confronts that the rise of education reformers dedicated to bureaucratic and technocratic reform as well as the concurrent reaction to that reform agenda among those championing an idealized faith in public education have in common their willingness to both trample and ignore the black and high-poverty communities, parents, and students both groups often claim to represent.

This education reform war, like Marvel’s Civil War, fails, as Perry has noted before, the problems of race and racism: “But let’s also stipulate that overwhelmingly white movements pursuing change for black and brown communities are inherently paternalistic.”

Perry concludes about the “overwhelmingly white” education reform wars: “We need less ‘reform’ and more social justice.”

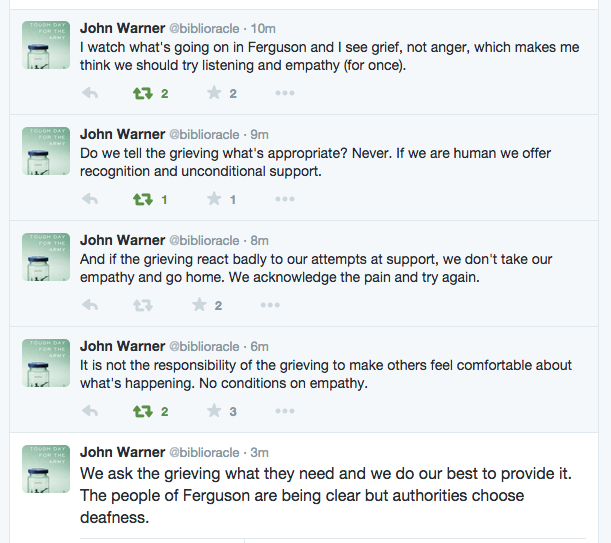

Posting on Twitter in the wake of the anniversary of Ferguson, John Warner strikes a similar chord in terms of broader failures of social justice advocacy:

While I entered public education dedicated to teaching as a form of activism for social justice, I can speak hear as someone who has certainly failed my own goals (confronting poverty and racism) by allowing much of my work both to feed and appear to feed the exact failure Perry and others have identified.

As I have been addressing for some time, the tensions of race and racism have been a central struggle of doing public work—although in my daily teaching, during my 18 years as a high school teacher and then more than a decade as a teacher educator, has remained more securely tethered to causes of social justice related to poverty and racism.

Lashing out against Teach For America and charter schools (among all school choice) by me and others has certainly served to ignore and even erase voices and issues connected to race.

But I also recognize the ineffectiveness of nuanced positions since my approach to Common Core has not fit within either the so-called reformer stance (pro Common Core) or the jumbled stance among idealistic public school advocates (some are for and some are against Common Core).

It is well past time, then, to emphasize that the recent thirty-years of education reform characterized by accountability built on standards and testing as well as the rise of TFA and charter schools would never have occurred if public education had been serving black and poor children as well as all formal schooling has served white and affluent children.

Education policy, then, is as complicated as social policy in the U.S.—where those in power and the public appear either reluctant or resistant to confronting the entrenched weight of race and class on social and educational equity.

And while political and public opinion are against us, those concerned with social justice linked to race and class equity must commit first to listening to and working with (not for) the communities, parents, and students who have been mis-served for decades by social and educational institutions and policies, specifically black and impoverished communities, parents, and students.

Missionary zeal and paternalism are burdens of both the education reformers and the public school advocates taking up arms against those reforms.

Broad stroke support for and rejections of any of these reforms are prone to be tone deaf and detrimental to claimed commitments for equity and social justice.

Evoking the very real and devastating realities mirrored in bad science fiction and Marvel’s Civil War, Perry argues: “New Orleanians don’t need an all-or-nothing, slash-and-burn system. We have inevitable hurricanes for that.”

And then:

Black folk are always the collateral damage of privileged people’s broad-stroke critiques. And the white criticisms of reform always negate black involvement and dare I say positive contribution toward change. We should validate the suffering, death and destruction that occurred during and in the aftermath of Katrina. But “awfulizing” isn’t the way to get there.

We don’t need the white, privileged, anti-reform framework developed by three or four white critics to deny the voices we need to uplift.

For me, the image I have evoked of political education reformers as the roadbuilders remains a valid metaphor, but it is incomplete and has too often served as just more noise drowning out those who must be heard.

So who is willing to stop the uproar against misguided and often tone-deaf education reform from the political elite long enough to listen to the black and poor communities who have witnessed decades of negligence by public institutions?

—

Reminder

Good intentions are not enough: a decolonizing intercultural education, Paul C. Gorski

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.