Teacher in a Strange Land: Racing, Striving, Accelerating, Winning. And Reading.

I wrote the core of this piece a decade ago, but it feels evergreen. Back then, we were trying to improve reading scores by offering kids rewards. Including pizza. Have we left competitive reading behind—or are ‘supplementary’ programs to raise scores, like Accelerated Reader, now being supplanted by the Faux Science of Reading?

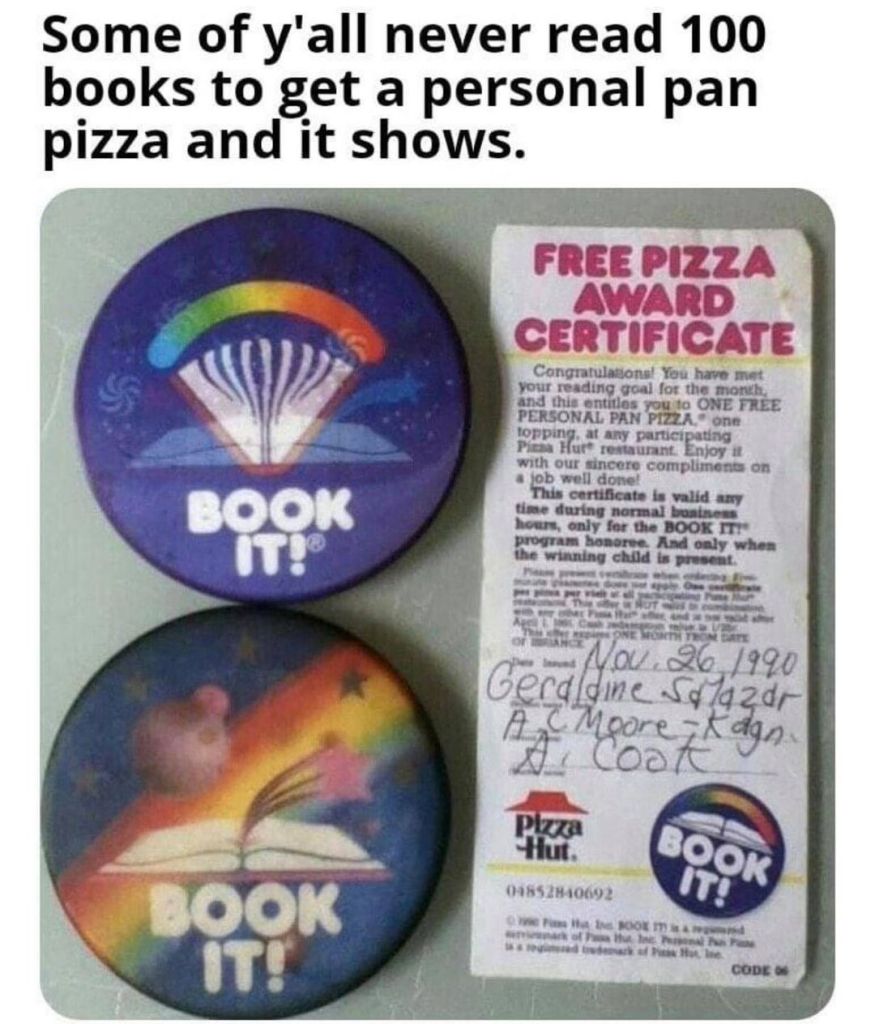

When my kids–now adults–were in elementary grades, their school participated in Pizza Hut’s Book It program. The idea was to promote reading by giving kids coupons for free individual pizzas if they read a specific number of books or were the “top” readers in their classes. Whole classes got pizza parties for reading the greatest number of books. Teachers and principal were solidly behind the program, promising public recognition for kids who read the most, silly adult stunts (from head-shaving to roof sitting) and assemblies if all classes achieved certain goals.

My daughter was immediately down with the Book It concept, strategically selecting and plowing through books to stay a volume or two ahead her classroom competitors. Soon, I was signing off on a dozen or more books per day–easy, short books–to keep her in the running for “best” reader. The free pizza coupons were piling up on the counter. It never was about the pizza, however. It was about the chart on the wall, where students tallied up their reading “scores.”

My son, on the other hand, was not a competitor. Both my kids–thank goodness–were early, fluent readers. He was reading a lot, at home, including car magazines and nonfiction books written for adults. But the Book It chart on the wall, the kids lining up every morning, excited to fill in the squares? Nope. He didn’t want to play.

He pointed out that his sister had taken to raiding the boxes of outgrown picture books in the basement, essentially juking her stats. Some of his buddies had only a couple of books listed on the chart (and they weren’t dumb). It was only suck-ups who were geeked about the long line of filled-in squares after their names. Another stupid contest.

After thinking about it for a few days, we agreed. I sent identical notes to teachers, saying that as a family we’d decided not to participate in competitive reading. Since I was also a teacher in the district, and not looking to make cranky-waves at my children’s school, I added some gently worded “I understand why you’re doing this–but no thanks!” language.

And that was that. Until I picked my son up one day and saw The Chart, with his name blacked out, and “Mom doesn’t believe in competition” carefully spaced out over all the empty boxes after the black mark. I asked the teacher why she wrote that–and she said she was trying to emphasize to the other 3rd graders that Alex wasn’t a poor reader or insubordinate. It was his mother who was responsible for Alex not being part of their rah-rah Book It team.

Whereas, of course, the kids with lots of empty boxes were incapable or defiant– not team players. You could tell, simply by looking at The Chart.

In the great scheme of reading instruction, Book It (which has changed its program in the meantime) is relatively benign compared to other reading-for-points programs. It’s just a cheesy (sorry) pizza-for-reading reward scam that gets “free” coupons with the Pizza Hut brand into homes and schools. It pushes kids to read for points and prizes, rather than pleasure and information. It emphasizes quantity over quality reading experiences, data over delight. It attaches a tangible (high fat) reward to an act that should be inherently exciting and deeply rewarding. And it slaps a big chart on the classroom wall so kids can readily identify winners and losers. It uses social pressure and food to force children to read competitively.

But other than that, no problem.

At least Book It (which is still being offered) doesn’t pretend to be a full-blown reading program. Nor is it offering cash for reading books, an experiment to see if paying kids for reading raises test scores.

The official competitive reading program du jour at my kids’ school was Accelerated Reader, and ultimately, research on Accelerated Reader was not encouraging. Stephen Krashen provided even more chilling findings on competitive reading programs:

Substantial research shows that rewarding an intrinsically pleasant activity sends the message that the activity is not pleasant, and that nobody would do it without a bribe. AR might be convincing children that reading is not pleasant.

If you think Accelerated Reader has had limited impact on reading programs in this country, check out this Pinterest page. Evidently, it’s not OK to simply read and enjoy a book anymore. You need a balloon to pop, a paper car to race, or public recognition for your Jedi reader status. You might also be asking questions about whether Accelerated Reader aligns with the Science of Reading, the new kid in town, reading-wise. Answer: not so much.

What to do, what to do? Contrary to popular opinion, how to teach reading is not “settled science.”

My friend Claudia Swisher, English teacher extraordinaire from Norman, Oklahoma taught a high school course called Reading for Pleasure. It was the antithesis of reading for points, pizza and pecuniary rewards. Claudia rejoiced when reluctant readers found enjoyment in reading and acted as book whisperer in helping them select engaging material. She talked with them about the books they read. She modeled reading herself, in every class. There were no tests. But her data showed that students grew, in measurable and immeasurable ways, from this experience.

Why aren’t all students reading for pleasure, every day?

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.