Janresseger: Educational Redlining: GreatSchools Ratings Drive Housing Segregation

Back in 2015, Heights Community Congress (HCC) in Cleveland Heights, Ohio raised serious concerns (here and here) about the impact of online GreatSchools ratings of public schools. The GreatSchools ratings were, in 2015, being used in online real estate advertising by listing services like Zillow. The practice continues.

HCC, founded in 1972, is Greater Cleveland, Ohio’s oldest fair housing enforcement organization. For over four decades HCC has been conducting audits of the real estate industry to expose and discourage racial steering and disparate treatment of African American and white home seekers. During 2015 and 2016, the fair housing committee of HCC held community meetings to demonstrate that such ads and ratings of public schools are steering home buyers to whiter and wealthier communities and redlining racially and economically diverse and majority black and Hispanic communities.

Last month, Chalkbeat published an in-depth examination of similar concerns on a national scale: “Arguably the most visible and influential school rating system in America comes from the nonprofit GreatSchools, whose 1-10 ratings appear in home listings on national real estate websites Zillow, Realtor.com, and Redfin. Forty-three million people visited GreatSchools’ site in 2018…. Zillow and its affiliated sites count more than 150 million unique visitors per month.”

Chalkbeat reports that GreatSchools has calculated its ratings for schools using the annual standardized test scores mandated by the 2002 No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), a requirement maintained in the Every Student Succeeds Act, which replaced NCLB in 2015. Because the ratings were criticized for relying too much on one standardized test score, in 2017, GreatSchools revised its algorithm for rating schools by including a factor to reflect the rate of growth in each school’s student test scores over time.

But Chalkbeat reports that the overall bias still condemns schools in the poorest communities: “When the organization overhauled its ratings in 2017, it included a host of new metrics. A GreatSchools representative said at the time that the new ratings would ‘more accurately reflect what’s going on in a school besides just its demographics.’ It was a striking acknowledgement of the flaws in the prior system… Two years into this new system, Chalkbeat took a closer look. We examined the ratings of elementary and middle schools in Chicago, Denver, Detroit, Indianapolis, Nashville, New York City, Phoenix, and San Francisco, combined with several of each city’s suburbs. The results are striking. On average, the more black and Hispanic students a school enrolled, and the more low-income students it served, the lower its rating. The average 1-10 GreatSchools rating for schools with the most low-income and most black and Hispanic students is 4 to 6 points lower than the average score for schools with the fewest black and Hispanic students and fewest low-income students. In most places, only a tiny fraction of schools with the most low-income and most black and Hispanic students score a 7 or better, the number that earns an ‘above average’ label from GreatSchools.”

In December, the National Education Policy Center (NEPC) reported on aNewsday report from Long Island: “The newspaper found that realtors repeatedly steered White buyers away from school districts enrolling higher percentages of minority residents, typically using veiled language. For example, they told white buyers that one community was an area to avoid ‘school district-wise’ or ‘based on statistics.'” And the housing values increased more rapidly in school districts with high GreatSchools ratings.

NEPC explains that Amy Stuart Wells, a professor of sociology and education at Teachers College, Columbia University followed up on the NewsDay report. Wells and her colleagues discovered that a one percent increase in Black/Hispanic enrollment corresponded with a 0.3 percent decrease in home values. In other words, a home worth $415,000 at the time of the study in 2010 would cost $50,000 more in a 30 percent Hispanic/Black district as compared to a 70 percent Hispanic/Black district.” Wells and her colleagues examined and compared the schools themselves: “There didn’t seem to be a huge difference at all in the curriculum and the quality of the teachers… So they (real estate agents) do play an important role in steering people away from certain districts that are becoming more racially, ethnically diverse and less White, in particular.”

For over half a century, research has confirmed that standardized test scores are a poor measure of the quality of a public school. Instead aggregate standardized test scores are highly correlated with family and neighborhood income. Children educated in pockets of privilege regularly post high scores, while children in schools where poverty is concentrated post the lowest scores. Here are three examples of this research, two by academic experts and the third a recent correlation study by the Cleveland Plain Dealer.

For a decade now, Stanford University’s Sean Reardon has been studying the correlation of achievement gaps measured by standardized tests with economic and racial segregation. He has documented that standardized tests measure all of the inside- and outside-of-school factors in a child’s life. Children who live in pockets of wealth bring their privilege with them when they take standardized tests. In a massive new study published last fall, Is Separate Still Unequal, Reardon explains: “The association of racial segregation with achievement gaps is completely accounted for by racial differences in school poverty.” “We examine racial test score gaps because they reflect racial differences in access to educational opportunities. By ‘educational opportunities,’ we mean all experiences in a child’s life, from birth onward, that provide opportunities for her to learn, including experiences in children’s homes, child care settings, neighborhoods, peer groups, and their schools. This implies that test score gaps may result from unequal opportunities either in or out of school; they are not necessarily the result of differences in school quality, resources, or experience. Moreover, in saying that test score gaps reflect differences in opportunities, we also mean that they are not the result of innate group differences in cognitive skills or other genetic endowments… Differences in average scores should be understood as reflecting opportunity gaps….”

Harvard University’s testing expert, Daniel Koretz, emphasizes that while children living in concentrated poverty take longer to catch up to their more privileged peers, our testing regime fails to consider the needs of children who start school farther behind: “One aspect of the great inequity of the American educational system is that disadvantaged kids tend to be clustered in the same schools. The causes are complex, but the result is simple: some schools have far lower average scores…. Therefore, if one requires that all students must hit the proficient target by a certain date, these low-scoring schools will face far more demanding targets for gains than other schools do. This was not an accidental byproduct of the notion that ‘all children can learn to a high level.’ It was a deliberate and prominent part of many of the test-based accountability reforms…. Unfortunately… it seems that no one asked for evidence that these ambitious targets for gains were realistic. The specific targets were often an automatic consequence of where the Proficient standard was placed and the length of time schools were given to bring all students to that standard, which are both arbitrary.” (The Testing Charade: Pretending to Make Schools Better, pp. 129-130)

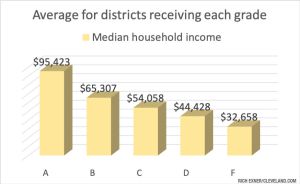

And finally, the Cleveland Plain Dealer‘s data wonk, Rich Exner created a series of bar graphs when the Ohio state school district report cards were

released last September. Exner demonstrates the correlation of the letter grades awarded to school districts by the state’s school rating system (letter grades based primarily on aggregate student’ standardized test scores) with the family income of the children in each school district. School districts earning “A” ratings boasted median family income of $95,432, while the school districts rated “F” serve families whose median family income is $32,658. The state of Ohio itself in its annual school report cards seems to be joining GreatSchools and Zillow to steer families to the affluent, white, exurbs surrounding our cities. These are the districts which regularly earn “A” grades on the state report card and the highest ratings from GreatSchools and Zillow.

It is alarming to see our society stepping back so completely from concerns about steering, disparate treatment, and redlining in the real estate market. These are the very issues the 1968 Fair Housing Act was intended to address. The National Education Policy Center declares: “Realtors and real estate websites alike share assessments that downgrade schools that serve higher percentages of low-income and minority students, while also serving to maintain segregated housing patterns by steering Whites away from districts that serve students of color.”

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.