Radical Eyes for Equity: The Big Lie about the “Science of Reading”: NAEP 2019 Edition

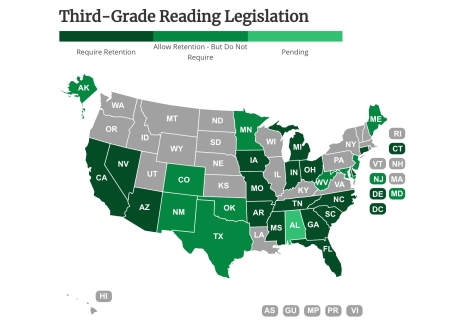

After the release of the 2017 NAEP reading scores, states such as Mississippi launched a campaign to celebrate the success of their reading legislation. This effort coincided with a recent explosion in states adopting reading legislation driven by dyslexia advocates who promote systematic intensive phonics for all students.

The claims coming from Mississippi didn’t seem credible, so I began what turned into a very long (and maybe endless) examination of the growing power of dyslexia advocates to drive what are essentially very bad forms of reading legislation, notably third grade retention and systematic intensive phonics for all students.

In my initial analysis of 2017 NAEP reading scores for 4th and 8th grades, I addressed the use of “the science of reading” as veneer for ideological advocacy; I also focused on the misuse by dyslexia/phonics advocates and the media of the National Reading panel and flawed claims about and definitions of “balanced literacy” and “whole language,” including mostly ahistorical understandings of how reading has been taught and discussed in political and public forums.

With the release of 2019 NAEP data, as we should expect, the same folk are back at over-reacting and misunderstanding standardized reading test data (mostly mainstream media), and dyslexia/phonics advocates are cherry picking evidence to reinforce their ideological advocacy.

All in all, these responses to NAEP data are lazy, and incredibly harmful.

Broadly, responses by the media and advocates have been overly simplistic, and lacking even a modicum of effort to tease out in a scientific way (ironic, eh?) mere correlations from actual causal associationsamong student demographics, reading policy, reading programs, the fidelity of implementing policy/programs, NAEP testing quality (how valid a proxy is NAEP reading tests for critical reading ability?), etc.

In a Twitter thread, I attempt to make a case against rushing to judgment based on 2019 NAEP reading data:

A little NAEP thread:

In 2017 MS made overstated claims about their NAEP reading scores, hiding the fact that 4th grade bumps disappeared by 8th grade and that NAEP scores remain mostly correlated with poverty; see:

The Big Lie about the “Science of Reading” (Updated)

2019 NAEP reading scores are likely to be a reboot of that for MS since 4th grade reading is an outlier among states in terms of gains but MS remains about average in 4th grade.

Only fair things to say about new round of NAEP reading scores:

• The US has never had a period over the last 100 years when we said “reading scores are where they should be.”

• There is always a claim of “reading crisis.”

• This is irrespective of how reading is taught.

• NAEP scores, like all standardized test scores, are mostly (60% +) correlated to out-of-school factors.

• NAEP scores only marginally about student achievement/reading, teacher/teaching quality, reading program effectiveness.

• NAEP scores are very pale proxies of readingRecent rounds of NAEP reading scores, however, are revealing how really bad reading policies (grade retention, intensive systematic phonics for all) can in the short term raise scores while likely deeply harming reading and readers. 4th-grade reading score bumps are mirages.

Equity gap between rich/poor reflected in NAEP reading scores amplifies the reality in the US that the rich get richer while the poor get poorer. Wealth = high achievement; poverty = low achievement. Student outcomes are a consequence of social negligence not student ability.

Placed in recent context of 2017 NAEP reading data and a wider recognition that student demographics (race, socioeconomic status) are historically and currently the greatest causal factors in student standardized test scores, the most fair argument to make in the wake of NAEP 2019 is that the matrix of reading policies and whether or not the policies are implemented at all or well (elements that we do not have data to support in any fashion) cannot be identified as success or failure. We may, however, be able to suggest that focusing on policy, standards, programs, and high-stakes testing simply does not change measurable reading outcomes in positive ways.

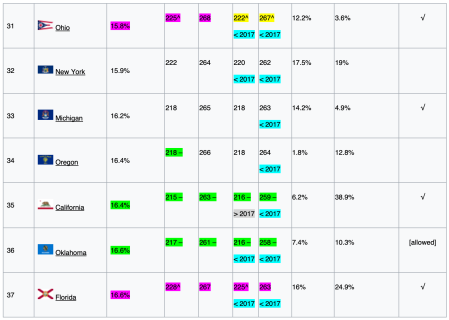

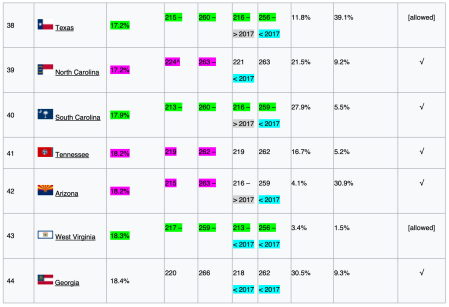

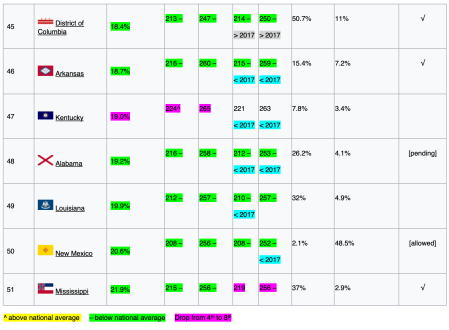

If you are fair and careful with the data I am including below, the correlations among all of the factors do not paint any clear picture at all about the effectiveness of programs or policy (again, even if we assume those programs and policies are being implemented at all or well).

Anyone using this data to claim “grade retention works” or “systematic intensive phonics works” is simply being deeply dishonest because no one has done any of the necessary work to tease out those claims in a scientific way (random sampling, controlling for non-instructional factors, investigating fidelity to policies and programs, etc.).

In other words, those advocating for the “science of reading” are making no effort to be scientific themselves in the pursuit of proving if their claims are valid, or not.

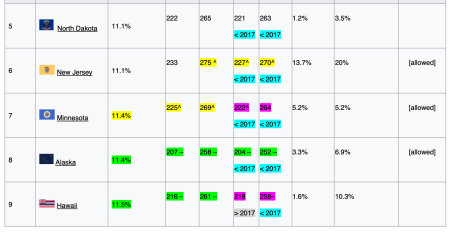

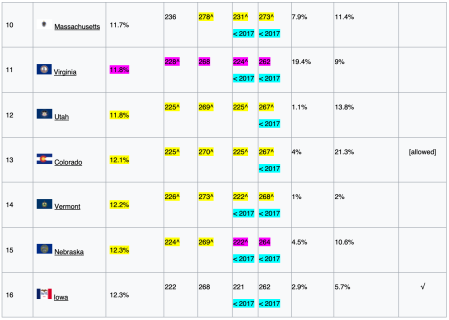

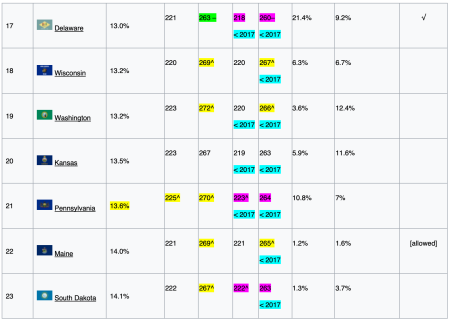

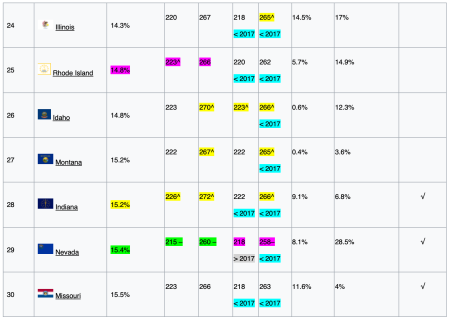

None the less, here are the updated data in a manageable chart:

If we genuinely believe a few points here or there, comparing entirely different populations of students under ever-shifting conditions both in their lives and in their education, are in fact not just statistically significant but significant, then we have a wealth of evidence above to suggest that all the standards, testing, and policies are actually degrading student reading achievement.

Finally, I want to stress, the greatest problem exposed by how the media and dyslexia/phonics advocates are responding to NAEP 2019 is that reading is too often a political and ideological football, and students in real classrooms and real lives are being reduced to petty games.

Again, at no point over the past 100 years have the crisis and failure arguments about reading achievement been any different than at this exact moment—regardless of how students have been taught to read (including peak years of intensive phonics and jumbled claims of implementing whole language).

How states mandate and implement reading instruction as well as relentlessly test it in the worst possible formats is a tale of too many cooks in the kitchen, with most of them having no credibility.

See Also

Third-Grade Reading Legislation

Third Grade Reading Policies (2012)

From Bruce Baker

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.