Gadfly on the Wall: Artificially Intelligent Chatbots Will Not Replace Teachers

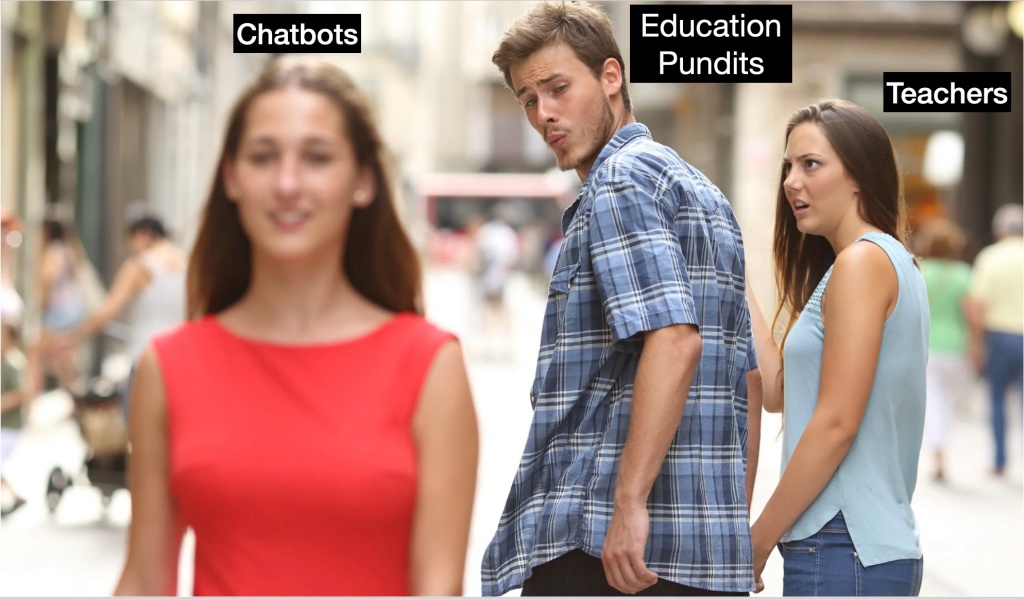

Education pundits are a lot like the guy in the “Distracted Boyfriend”meme.

They’re walking with teachers but looking around at the first thing possible to replace them.

This weekend it’s AI chatbots.

If you’ve ever had a conversation with Siri from Apple or Alexa from Amazon, you’ve interacted with a chatbot.

Bill Gates already invested more than $240 million in personalized learning and called it the future of education.

And many on social media were ready to second his claim when ChatGPT, a chatbot developed by artificial intelligence company OpenAI, responded in seemingly creative ways to users on-line.

It answered users requests to rewrite the 90s hit song, “Baby Got Back,” in the style of “The Canterbury Tales.” It wrote a letter to remove a bad account from a credit report (rather than using a credit repair lawyer). It explained nuclear fusion in a limerick.

It even wrote a 5-paragraph essay on the novel “Wuthering Heights” for the AP English exam.

Josh Ong, the Twitter user who asked for the Emily Bronte essay, wrote, “Teachers are in so much trouble with AI.”

But are they? Really?

Teachers do a lot more than provide right answers. They ask the right questions.

They get students to think and find the answers on their own.

They get to know students on a personal level and develop lessons individually suited to each child’s learning style.

That MIGHT involve explaining a math concept as a limerick or rewriting a 90’s rap song in Middle English, but only if that’s what students need to help them learn.

It’s interpersonal relationships that guide the journey and even the most sophisticated chatbot can’t do that yet and probably never will have that capacity.

ChatGPT’s responses are entertaining because we know we’re not communicating with a human being. But that’s exactly what you need to encourage the most complex learning.

Human interaction is an essential part of good teaching. You can’t do that with something that is not, in itself, human – something that cannot form relationships but can only mimic what it thinks good communication and good relationships sound like.

Even when it comes to providing right answers, chatbots have an extremely high error rate. People extolling these AI’s virtues are overlooking how often they get things wrong.

Anyone who has used Siri or Alexa knows that – sometimes they reply to your questions with non sequiturs or a bunch of random words that don’t even make sense.

ChatGPT is no different.

As more people used it, ChatGPT’s answers became so erratic that Stack Overflow – a Q&A platform for coders and programmers – temporarily banned users from sharing information from ChatGPT, noting that it’s “substantially harmful to the site and to users who are asking or looking for correct answers.”

The answers it provides are not thought out responses. They are approximations – good approximations – of what it calculates would be a correct answer if asked of a human being.

The chatbot is operating “without a contextual understanding of the language,” said Lian Jye Su, a research director at market research firm ABI Research.

“It is very easy for the model to give plausible-sounding but incorrect or nonsensical answers,” she said. “It guessed when it was supposed to clarify and sometimes responded to harmful instructions or exhibited biased behavior. It also lacks regional and country-specific understanding.”

Which brings up another major problem with chatbots. They learn to mimic users, including racist and prejudicial assumptions, language and biases.

For example, Microsoft Corp.’s AI bot ‘Tay’ was taken down in 2016 after Twitter users taught it to say racist, sexist and offensive remarks. Another developed by Meta Platforms Inc. had similar problems just this year.

Great! Just what we need! Racist Chatbots!

This kind of technology is not new, and has historically been used with mixed success at best.

ChatGPT may have received increased media coverage because its parent company, OpenAI, was co-founded by Tesla Inc. CEO Elon Musk, one of the richest men in the world.

Eager for any headline that didn’t center on his disastrous takeover of Twitter, Musk endorsed the new AI even though he left the company in 2018 after disagreements over its direction.

However, AI and even chatbots have been used in some classrooms successfully.

Professor Ashok Goel secretly used a chatbot called Jill Watson as an assistant teacher of online courses at the Georgia Institute of Technology. The AI answered routine questions from students, while professors concentrated on more complicated issues. At the end of the course, when Goel revealed that Jill Watson was a chatbot, many students expressed surprise and said they had thought she was a real person.

This appears to be the primary use of a chatbot in education.

“Students have a lot of the same questions over and over again. They’re looking for the answers to easy administrative questions, and they have similar questions regarding their subjects each year. Chatbots help to get rid of some of the noise. Students are able to get to answers as quickly as possible and move on,” said Erik Bøylestad Nilsen from BI Norwegian Business School.

However, even in such instances, chatbots are expensive as yet to install, run and maintain, and (as with most EdTech) they almost always collect student data that is often sold to businesses.

Much better to rely on teachers.

You remember us? Warm blooded, fallible, human teachers.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.