Curmudgucation: Annual NAEP Panic (COVID Edition)

It's back. The annual-ish exercise in trying to read test-driven tea leaves that is the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), undeservedly called "The Nation's Report Card."

The NAEP results are a data-rich Rorschach test, telling us far more about the people interpreting the data than the data itself (in fact, the biggest lesson of the NAEP is that data doesn't actually settle a damned thing).

But this year we get a bonus--the NAEP Pandemic Finger Pointing Edition! Yay.

News outlets are mostly sticking with bare bones reporting (with the exception of the New York Times, which we'll get to in a moment), like the Washington Post's headline over the AP story "Reading, math scores fell sharply during pandemic, data show."

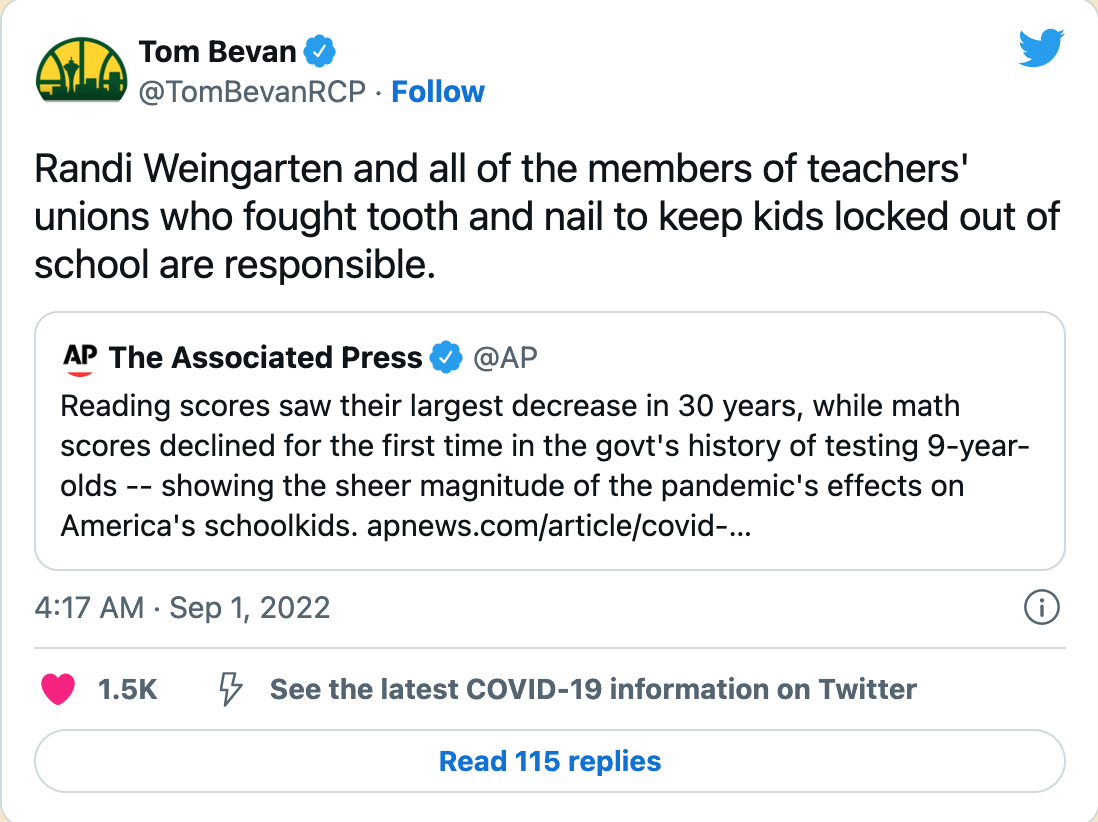

But on the Tweeternet, plenty of folks are pouncing with the argument they've just been waiting to make. Here's Tom Bevan, head guy at right wing Real Clear Politics--

You know this story already. For some reason, a couple years ago the teachers unions closed down US schools and kept them closed for no reason at all. Certainly not because there was a pandemic killing people and information about how to handle it was sparse and the feds said "Hey, you're on your own. Figure something out." I don't want to wander too far down this rabbit hole, other than to note that if teachers have the power to shut down the country, you'd think they'd use it for other things, like getting money and resources. And the "lazy teachers don't want to work" explanation would make more sense if remote pandemic school weren't actually twice as much work for teachers as the in-building type. And I am tired of people on all sides ascribing various sinister motives to people who were mostly scared and trying to do the best they could in a frightening and life-threatening situation, and lacking dependable information, lots of people made lots of different decisions and for heavens sake, is it that hard to exhibit a little kindness and empathy even if it's not politically expedient?

You know this story already. For some reason, a couple years ago the teachers unions closed down US schools and kept them closed for no reason at all. Certainly not because there was a pandemic killing people and information about how to handle it was sparse and the feds said "Hey, you're on your own. Figure something out." I don't want to wander too far down this rabbit hole, other than to note that if teachers have the power to shut down the country, you'd think they'd use it for other things, like getting money and resources. And the "lazy teachers don't want to work" explanation would make more sense if remote pandemic school weren't actually twice as much work for teachers as the in-building type. And I am tired of people on all sides ascribing various sinister motives to people who were mostly scared and trying to do the best they could in a frightening and life-threatening situation, and lacking dependable information, lots of people made lots of different decisions and for heavens sake, is it that hard to exhibit a little kindness and empathy even if it's not politically expedient?

Or, in shorter terms, yes, the choices about schools open or closed was made politically, but if you're ignoring the context--a pandemic that killed over a million Americans--you're being deliberately obtuse.

Anyway, the NAEP is going to get us that again, blaming the score drop on forced distance learning (where children had to stay at home and learn via computer) and blaming forced distance learning on the teachers unions. Ironically, some of this will come from some of the same people who promote things like microschools (where children stay home and learn via computer).

The absolute worst headline of the day (and it was by God up at 12:01 AM, presumably when the press embargo ended) belongs to the New York Times. Let's take a look, because this captures so much of what is wrong with journalism's coverage of test scores:

The Pandemic Erased Two Decades of Progress in Math and Reading

What the heck does that even mean? Whose progress, exactly? This is talking about test scores as if they are toaster production numbers, as if they are a politician's poll numbers, as if test scores are like the stock market, as if schools are a modern capitalist enterprise that must "produce" bigger numbers each year or else it's a failure, as if the pursuit of test scores can be bent to standard horse race coverage.

Are they suggesting that schools lost "progress" in pedagogical technique, that the pandemic somehow knocked schools back to functioning as they did twenty years ago? Teachers forgot everything they learned in those two decades? The nine year old students have somehow rolled back to -11 in their learning curve? That this is not a blip caused by a singular and unprecedented interruption of schooling, but some kind of reset, some time traveling blip. Dammit--does this mean my retirement has been rescinded? And could there be any other explanation for the drop in score?

The story (not the headline--never blame the newspaper headline on the writer) is by Sarah Mervosh, and it calls for all the clutching of pearls. Test scores post pandemic are now down several points to where they were twenty years ago. Which is bad because...?

The setbacks could have powerful consequences for a generation of children who must move beyond basics in elementary school to thrive later on.

Must they? Are the consequences powerful? Have we, for instance, tracked the generation from twenty years ago and found that those test scores are indicative of a generation of failures, haunted forever by their crappy NAEP scores? Because previous research suggests that plenty of low-NAEP score students do just fine. But we're going to pull some more scary quotes:

“Student test scores, even starting in first, second and third grade, are really quite predictive of their success later in school, and their educational trajectories overall,” said Susanna Loeb, the director of the Annenberg Institute at Brown University, which focuses on education inequality.

“The biggest reason to be concerned is the lower achievement of the lower-achieving kids,” she added. Being so far behind, she said, could lead to disengagement in school, making it less likely that they graduate from high school or attend college.

But correlation is not causation. Correlation is not causation. Correlation is not causation.

More importantly, that correlation is what happens in normal times, which the last three years have not been. Are student now dumber than they used to be, or did these students not get quite as much formal learning done because there was a pandemic going on? Or should we conclude that less formal schooling meant less formal test prep training, and that smart kids who would have been successful may not have tested up to par, but will recover and do fine?

And more more importantly, does raising test scores raise life outcomes? (Spoiler alert: no research says that it does).

I'm not saying that last option is certain. I am saying that coverage routinely ignores it, because--and this has never ceased to be annoying--journalists insist on accepting standardized test scores as valid and useful proxies for student achievement (and that artificially created benchmarks somehow descended from heaven on stone tablets). There is simply no reason to believe that they are, but they're numbers and easy to work with and sound really official.

Nor has there been any context given to today's numbers. Back in 2019, head of NCES Peggy Carr was saying this:

“Since … 1992, there has been no growth for the lowest-performing students in either fourth-grade or eighth-grade reading,” she said. “That is, our students who are struggling the most at reading are where they were nearly 30 years ago.”

Nor are we taking much notice of the fact that these are just 4th grade scores, and a lot of things happen between 4th and 12th grade to those scores (like in Florida, where they utterly collapse year after year).

One thing does remain true, albeit unsurprising-- schools that serve poor students, schools that are under-resourced, show far lower scores than other schools. I predict that once again this year policy makers will look at that data and conclude everything except, "We should get more support and resources to those schools."

Not that some folks don't have ideas. Mervosh talked to Martin West at Harvard Graduate School of Education and a member of the board that oversees the test, and it turns out he knows how to solve the problem of educational inequity in this country. Dr West said "that low-performing students simply needed to spend more time learning, whether it was in the form of tutoring, extended school days or summer school."

“I don’t see a silver bullet,” Dr. West said, “beyond finding a way to increase instructional time."

That might not be the silliest thing I've ever seen from a college professor of education, but it comes damn close.

Oh well. Let's move on to the next part of the annual ritual. Pearls will be clutched. People will claim the data proves the things they always argue for anyway. No actual action will be taken. And the storm will pass. And teachers will go back to teaching students as best they can, including meeting them where they are. Happy NAEP.

This blog post has been shared by permission from the author.

Readers wishing to comment on the content are encouraged to do so via the link to the original post.

Find the original post here:

The views expressed by the blogger are not necessarily those of NEPC.